Welcome to your first day of training, space cadets. I am captain

You will be engaged in a series of training sessions that we’ll perform while orbiting the planet called “Earth.” it is active learning and you will absorb a lot of knowledge as we go on. Your training will be dedicated to refining your observation capabilities. It is a skill you will surely use when you explore other planets of the galaxy.

Before starting, let me tell you a few basic things. First, we are following a rule that says we do not harm the creatures we study. And not just that, we do not make them suffer or feel uncomfortable. We respect the creatures we encounter; it is the fundamental rule of the reptilian Starfleet, of which you will be proud officers. So, we may lift living specimens from the planet we are orbiting around, but we’ll ensure they are not mistreated.

We are now orbiting around the third planet of this star system. You have already seen it when we emerged out of hyperspace a few time units ago. You are seeing it now, from the screens of our ships. It is partly blue, white, and green. These colors are typical of planets full of biological life: the creatures inhabiting it are based on some of the same metabolic and molecular processes that we reptilians use.

I have to explain what we mean by “naked ape.” First, note that to indicate the creatures of this planet, we are using mostly terms that we borrowed from the naked apes themselves. They are smart, and their scientists are almost as good as ours. So, we can make profitable use of the database they accumulated in their observations. They use the term “ape” for a variety of rather large, mostly arboreal creatures. Most of them are not naked; they have fur. The specific creatures we are examining, instead, have almost no fur. Actually, most hot-blooded animals on this planet have fur, making the naked apes even more exceptional. Note also that these creatures don’t refer to themselves as “naked apes.” They rather use the term “humans,” But we’ll often use the term “naked ape,” which we think is a good description of what these creatures are.

So, let’s start with your first exercise. We’ll go directly into the examination of one of the naked apes. Here is a specimen, a young male that we lifted from the planet's surface. Let’s have him stand on the platform; you can see him well. He is lightly sedated because he might fear your presence, and we don’t want to upset him. Note that we’ll strictly adhere to our Starfleet ethical regulations throughout these learning sessions.

Get close; the creature is relaxed, and he won’t hurt you, although, from his viewpoint, he may find you unattractive or even repulsive. Of course, it is the same for you about him but, as space cadets, you must learn to approach and deal with all sorts of creatures.

Note the flexible layer that covers most of his body's central part. It is not fur; it is not skin: it is an

exoderma that these creatures manufacture to cover their bodies. Only these creatures have this use on the whole planet. In this specific case, the exoderma is very thin and light. In other cases, it may be heavier and thicker and cover the creature nearly completely. In most cases, it is made of vegetable fiber – these creatures are clever at processing vegetal materials. They also use fibers obtained from fossil hydrocarbons - very clever, indeed. Sometimes, they also use the skin of other animals, which they can treat in such a way as to make it flexible. See the exoderma over the creature’s feet? Yes, it is made of the treated skin of another mammal. I told you that they are rather special, and this is one of their unique characteristics.

We said this is a naked ape, it means it has no hair over his body. But you can see he is not completely naked. He has hair on the top of his head. By removing the exoderma, you might also see that he has hair around his genitalia. For some reason, though, they are very sensitive about showing that area, so we won’t embarrass him by forcing him to show it -- we continue to apply the Starfleet standard to avoid creating discomfort for the creatures we study. And, of course, he has sparse hair all over his body, but so sparse that you can rightly define him as a “naked ape.” Some subspecies, those with a dark skin color, actually have no hair over their bodies.

Now, let’s examine this specimen even more closely. Approach him gently; as I said, the creature is lightly sedated, but it might still perceive you and be afraid of you. Note the light color of his skin; it is nearly white, although it shows a shade of pink. The pink color is the result of the presence of a red molecule they use to transport oxygen around the body. They call it “hemoglobin,” they are clever chemists, these apes. This pink skin is only one of the several shades of color that their skin can show. Some of them have much darker skin, sometimes dark brown and, in some cases, nearly black. It is because of another molecule that they secrete in the skin layer. It is called melanin. They use it to avoid damage from the ultraviolet radiation from their sun. These white ones live in Northern or southern latitudes, where the star's radiation is not so strong, so they don’t have melanin. The apes living closer to equatorial latitudes are typically dark-skinned -- plenty of melanin they have. We chose a white specimen because the lack of pigment makes it easier to examine the skin. Still, the genetic differences among the differently colored naked apes are small.

Now, cadets, you can touch the skin of the specimen. Do it gently, do not upset him, but do it and tell me your impression.

-- It is very soft, Meuianga.

-- Yes, soft and mobile. It is remarkable that they have this soft skin. It doesn’t protect them from anything.

That’s very good,

Stäpxrä Te Äpxtìkwie Upvi'itan. Can someone tell me more?

-- Captain, really, I wonder why it is so soft.

Räuväwao Te Nguaär Lawarlewr'itan, can you guess why?

-- There is a sort of cushioning layer underneath, Meuianga.

-- Yes, it is thicker in some areas.

-- It sticks to the skin. It makes it soft.

Yes, it is soft. The skin sticks to the layer underneath. And I can tell you that, right below the skin, there is a layer of fat. You know that fat molecules are long hydrocarbon chains that form soft solids. The fatty layer under the skin of this specimen makes their skin soft but relatively solid. We might experiment with other mammal species from Earth, and you would easily note that their skin is much more pliant and less adherent to the muscles below. It is because they don’t have this thick layer of fat. Now, can you guess what this fat is for?

-- Captain, might it be for thermal insulation?

Very good, Nìsrr Te Yuoit Tatxapkìpx'ite! If I were to use a term that the apes like, I would say, “Bingo!” It is an exclamation indicating a pleasant surprise. Although I must say that we never understood what this “Bingo” is about, a sort of religious ritual, we believe. Anyway, yes, this fatty layer is a thermal insulation system, but not just that. Indeed, you noticed that it is much thicker in some areas, where it forms protuberances. That’s especially true for their females: they have prominent frontal protuberances that males don’t have. These protuberances are full of fatty acids, they are used as energy storage areas. Their metabolism can use fatty acids as an energy source. In this, they are not special. Most warm-blooded creatures on the planet store energy in fatty areas; even some cold-blooded ones do.

Now, let’s go on with our examination. I would ask now to use your sense of smell. Cadets, would you get close enough to smell the skin of this specimen? Yes, do it.

-- Yes, the creature has a peculiar smell.-- But the skin is wet in some places.

-- Especially near the armpits. It is wet, and it smells of organic molecules.

Very good, cadets. Especially you, Yiìzen Te Yaay Siurä'ite, you identified one of the smelling areas of the creature. It is the armpits. They can produce quite a lot of liquid there. It is called “sweat;” a typical secretion of these creatures. But they produce it all over their bodies, using specific “sweat glands.” It is mostly water, together with some organic molecules. For what you need to know, all the mammals of planet Earth produce sweat. You may be curious to know that the other major group of hot-blooded creatures of the planet, those called “birds,” do not sweat at all. They just do not have sweat glands. It is another interesting feature of the biosphere of this planet.

Now, there is something that you could perceive only using specific instruments, but I’ll just tell you about it. These creatures have a huge number of sweat glands on their bodies. A specimen like this one may have 2-3 million glands. And they can secrete as much as three liters of water in an hour, which is remarkable. No other creature on Earth can sweat so much. The sweat also contains “pheromones,” volatile molecules that the creatures use for sexual signaling.

-- Really? But don’t they dry out their metabolic system?-- Yes, how can they replace all that water?

-- Don’t they harm themselves in this way?

Cadets, these are all legitimate questions. Now, to answer them, we’ll go to a more detailed description of the metabolism of these creatures. I see that you already gained some familiarity with a specimen of the naked apes -- they call themselves “humans.” I can tell you that they are fascinating, indeed. I have been working on studying them for more than two hundred orbital revolutions of their planet -- they call those revolutions “years.” And it has been a learning experience that taught me many things.

The question is, why are they naked? You’ll see that there is a reason why these creatures evolved to become naked as they are. But first, we need to start by placing them in the context of their ecosystem. As you already know, Earth is a relatively cold planet. And you also know that the metabolic processes of carbon-based life work best at temperatures of about 35-40 °C. Now, Earth’s average temperature is only 15°C. It is also a planet of rapid temperature changes, resulting from its rotation axis being tilted compared to the orbital one. This means the earthlings’ main problem is keeping warm enough to keep their metabolism functioning. And that’s the purpose of hair. It is a little like our scales, but it is an ensemble of filaments that trap air between them, and air is a good thermal insulator. Some creatures on Earth use a more sophisticated covering layer, elaborate structures called “feathers,” but the idea is the same: trap air in between and slow down the loss of heat.

Back to the naked apes, the first element to consider is that mammals about the same size are not naked. Practically all of them are covered with fur. Only elephants, hippos, rhinos, and a few other land mammals do not have hair over most of their bodies. That makes sense: a large animal has a low surface to volume ratio, so it doesn’t cool down so easily. The problem for large animals is how to keep cool rather than how to keep warm. Nevertheless, in cold climates, even large animals sport thick fur. Think of the mammoths, large creatures living on Earth a few million years ago. You have seen images of them in your training material. You saw how furry it was. Funnily, the naked apes have become good enough at genetic engineering that they are thinking of reviving the mammoths. I think they might even succeed, but let’s skip that.

The trend is the opposite on another part of the planetary ecosystem, the seas. Most marine mammals are not hairy: whales, dolphins, and the like have no hair. Only some creatures with a hybrid lifestyle have hair: seals, walruses, and also penguins (they use feathers, but it is the same mechanism). And that’s logic, again. Hair is good for insulation, but, as I said, it is because it incorporates a lot of air. But that won’t work underwater. So, these marine creatures are covered by a thick layer of fat that insulates them. No need for hair.

We conclude that a land creature that’s not too large should have hair. Then, why these curious apes are naked? I must tell you that the question puzzled me for quite a while. I remember having discussed it with one of the ape scientists, long ago; his name was Charles Darwin. He lived nearly two hundred Earth-years ago; I was young then! A very special ape: he never found my green scales upsetting. He understood right away who I was and where I was coming from. Most of the apes who are not scientists will run away screeching when they see one of us. Unless we use one of our mirage mantles, but let me not go into that. I have a picture of him that I can show you. Unfortunately, these apes don't live long, so he is not there anymore. Note that he was quite hairy himself! Here you see him and me chatting. I am wearing one of our mirage suits -- I look fully human! The picture is made with a camera made by the apes -- only black and white images at that time.

Anyway, when I met Charles (we became good friends, and for apes, it means addressing each other by what they call the “first name), he was engaged in trying to understand why the human apes -- and himself, too -- are naked. You know, he was the first ape to develop a reasonable version of the natural selection theory, the force that moves the universe. He hadn’t yet arrived at the concept of “holobiont,” the universal thermodynamic dissipation structure, but he was quite advanced in the right direction. Yet, he couldn’t understand why the human apes were naked. And I couldn’t help him; I still had so many things to learn at that time. I just remember that Charles showed me something written by another ape scientist, Alfred Wallace his name, who attributed the nakedness to a kind of “super-ape” floating in mid-air, just above the clouds. This story would need some time to be explained; anyway, several apes say that this super-ape can create things and animals at will. For some reason, he (the super-ape, they see him as a male) wanted the human apes to be naked -- maybe because he was naked himself. Don’t ask me how it is that they can think such weird things. It is beyond me. These smart apes can be quite dumb sometimes.

But don’t dismiss the ape scientists. They can be very good at their job, and they never were comfortable with the idea of a super-ape flying in the sky. So, they tried to find a good explanation, but it was hard for them. Poor Darwin, for instance, proposed that humans would find each other more sexually attractive by being naked. I asked him why, and he could only babble something not so coherent. I can only imagine that modern apes do find other naked apes more attractive when they are naked, but that it could be true for their remote ancestors; well, it is hard to maintain. I can only imagine that modern naked apes do find other apes more attractive when they are naked, meaning without their exoderma. But could that be true for their remote ancestors? Why should that be? Besides, there is always the same problem: why wouldn’t natural selection cause apes of other species to shed their hair to appear more attractive to their sexual partners?

Besides, there is always the same problem: why won’t other apes use the same trick to appear more attractive to their sexual partners?

Oh, they worked hard to propose the strangest explanations. One was that being naked made it easier for human apes to detect parasites and de-louse each other. Nice idea, but, then, why did they maintain hair over their head and around their genital area? These areas are normally full of parasites. Incidentally, you may like to know that different species of lice infest these two different areas of the human body. It is a curious detail, but it shows that their nakedness is ancient -- a typical effect of natural selection.

Then, someone proposed an effect called “neoteny,” the idea that evolution occurs by species maintaining their juvenile traits, in this case, the traits of fetuses -- which obviously have no hair: what would that help them for while they are inside their mother’s womb? And, yes, there is some evidence of neoteny in modern naked apes but, again, this is not really an explanation. Most mammal fetuses are hairless, but only the human ape is hairless as an adult. And why should that be?

One of the strangest theories was proposed by an ape named Alister Hardy. He surmised that the human apes had been marine mammals earlier in their evolutionary history. So, like all marine mammals, they had lost their hair and developed a layer of subcutaneous, insulating fat. And that they had maintained this characteristic once they had returned to land. I never met this Hardy, but I read about his theory in the ape scientific literature. Surprisingly, the theory became very popular and some ape scientists still consider it at least a possible explanation. But it left me perplexed. Highly perplexed. By then, I had already developed the theory that explains the apes’ nakedness. But let’s go step by step.

I guess it is not difficult for you, cadets, to understand why this theory of the “aquatic ape” doesn’t make much sense. As part of your training, can someone provide a suggestion on this point?

-- Meuianga’ Enge’ite, I think such a theory can be proposed, but the criticism is obvious: does it have any proof?

-- Yes, Meuianga, we read in our training material that some land mammals moved to the sea, but I didn’t find any notion that the reverse happened.

-- And, besides, Meuianga, if these apes had been aquatic for a certain period, why didn’t they regain their hair when they moved back on land?

Very good cadets. Indeed, you are getting into the matter we are discussing. The theory of the aquatic ape doesn’t make sense exactly for the reasons you identified. There is no proof for it and, besides, if these apes returned to land, they should have regained their hair and lost their fat. You may be interested to learn that the only “proof,” so to say, that the ape scientists favoring this idea could produce was to refer to some old legend of theirs that tell of “merfolk,” aquatic apes, indeed.

-- Aquatic apes, Meuianga? Do they exist? We didn’t read of them in our training material.

-- And what would be this thing you mentioned, a “legend”?

Ah, sorry, cadet Ngìrtsmokxpäay Te Loro Wukxer'itan. I think the concept of “legend” was not explained in the training material you studied. So, let me tell you something about it. A legend is a peculiar form of thought that derives from the brain setup of the naked apes. It appears that they are wired to believe things that do not exist, or that couldn’t even exist. They believe in purely mental constructions that they build in their brains. This is true about the merfolk legend, creatures that are half ape and half fish. They are supposed to be male and female; the first kind is called mermen, and the other mermaids. Let me show you a metal cast image made by an ape about one hundred Earth-years ago. Here it is; you can see it on your screens. Note how the legs have fins.

-- That’s a fascinating image, Meuanga. But this creature doesn’t make sense. It can’t walk on land: look at the fins!

-- And it has those arms without fins. Not good for swimming.

-- Can it catch fish while swimming? It doesn’t have fangs.

-- It doesn’t seem to be able to eat plankton. Its mouth is too small.

You are right, cadets. This is not a real creature. It is a representation of the legend of the merfolk.

-- But why would the apes make an image of a creature that can’t exist?

-- Are they dumb? Or are they confused?

-- We cannot understand that. Are these “legends” a mental sickness?

Cadets, don’t get so perplexed. In time, you will understand. The naked apes are neither dumb nor confused. And they don’t normally suffer from mental problems -- although some do. But let’s focus on the point that we were making. We were looking for a good explanation of why they are naked while most of the other mammals on the planet are not and, clearly, the idea that they were marine mammals long ago cannot work. Cadet Zäut Te Kawvei Tstxìa'ite, can you propose a different explanation?

-- Well, Meuianga’ Enge’ite, I was thinking of something you were telling us. The apes live on a cold planet, still they may have problems of overheating when they are very active. Captain Pxaymeflae'itan told us about their sweat glands. And I was wondering… hair is for keeping warm, but how would it affect these creatures' cooling mechanism?

Excellent, cadet, excellent.

-- Meuianga, you make my scales flutter. I don’t deserve this praise.

It is fine, cadet Tstxìa'ite. You and your colleagues are all smart reptiles, and you are all learning plenty of things. I praised you as just a way to praise you all. But let’s go back to what we are discussing. Captain Pxaymeflae'itan told me that he had you smell the skin of this creature, right? Did you notice how wet it is?

-- Yes, Meuianga. We noticed the smell. Captain Pxaymeflae'itan told us about the high density of sweating glands they have. Is that related to the fact that they are naked?

Yes, cadet. And that’s the crucial point that explains the whole story. I think you all understand how things stand; I see that from your flickering nictitating membranes. Yes, These creatures evolved by shedding their fur to be able to cool down faster by sweating profusely. Their metabolism is outstandingly fast. No other creature on the planet can keep going so long and so intensely. This is a point that ape scientists started making some 50 Earth-years ago. One of them was named Desmond Morris and he had this idea of calling his own species the “naked apes.” He wrote at length about this idea and I learned this definition from him. I think it is a very good description of these apes. It is curious, though, that it didn’t become popular with the apes themselves -- it is mostly us, the reptiles, who use it. In any case, it is the basic point of why these apes are naked. They can cool their body when they are engaged in strenuous efforts.

-- Does that mean that they can outrun other mammals, Meuianga?

Not really outrun, cadet Aymaopta Te Uutlei Raonga'itan. Running fast is not the point of their cooling setup. They are endurance runners. They can keep running longer than most other mammals. In this way, they can wear down their prey. They keep running until the prey is exhausted, then they close in for the kill.

-- Meuianga, this is hugely interesting. But is it a good way to kill their prey? It seems to require a lot of effort.

-- Why don’t they do like us? We reptiles don’t need to run for a long time after our prey. We ambush it, jump on it, and kill it.

A good observation, cadet Äuhen Te Ifue Txote'ite. And you are right; if they were to hunt always as I described, it would be a big waste of effort. Their way of hunting is more sophisticated; they can be good ambushers and jump on the prey when they have the occasion to do it. They are also good group hunters. You know, their scientist found proof that a group of them could push entire herds of mammoths or other large mammals down a cliff and kill all of them.

-- Oh, that looks like a wasteful way of hunting, Meuianga.

-- Do they really do that?

-- You said that they are smart, Meuianga. But if they behave in this way, well, maybe they are not so smart.

It is a long story, cadets. Indeed, naked apes sometimes behave in ways that don’t look so smart. This idea of killing entire herds of big animals is typical of them. They can behave in highly wasteful ways, even today, when there are no more mammoths on their planet. And the reason why there are no mammoths anymore is probably that they killed so many of them long ago. It is just the way they are. You must understand the species you encounter; they are not like us. What they do is because of what they are. But this is what they are: powerful creatures that can keep running when other animals become exhausted.

-- But, Meuianga, excuse me, can I ask a question?

Of course you can ask a question, Ilau Te Muiotäk Viiskewa'ite.

-- Meuianga, if the trick to gain this high metabolic power is to become naked, why don’t all mammals do that? I think it may not be a good idea for small mammals, but we read in our training materials that there are many animals as large as the naked apes, but they are not naked.

Very good, cadet Viiskewa'ite. This is exactly the spirit of these lessons. You ask questions and try to understand the matter you are studying. You see, we discussed how to explain why being naked, that is without fur, can be advantageous for a high metabolic rate mammal. But you are correctly asking, “if it is so advantageous, why do only the human apes use it?” Good question, indeed. Not even Desmond Morris could answer it, although he got close to finding it. Can someone propose why that could be?

-- Meuianga, we must admit that we are baffled.

-- Yes, just as baffled as your friend, the ape scientist Charles Darwin.

-- There must be a reason, but we can’t find it.

-- Maybe the naked apes were really created by a super-ape floating in the sky?

Oh, that’s a nice one, cadet Viiskewa'ite. You may like to know that you are using the same logic that sometimes the naked apes use. When they can’t understand something, they say it is because of something that the super-ape in the sky did. They can be really funny, but it is the way they are. But you are cadets of the proud Reptilian Starfleet, and you can arrive at an answer. You may just need a little help. First, it should be clear to you why land mammals cannot afford to sweat.

-- Because they lose water too fast, Muienga?

Exactly. For an animal, it is dangerous to sweat too much. They may get dehydrated. And they can die unless they find a water source, quickly. Besides, stopping to drink at a lake or a river is always dangerous. It is there that predators wait to ambush them; it is the reptile strategy that our ancestors used. So, most land animals on Earth sweat very little, that's typical of mammals. Or even don’t sweat at all: Earth’s birds have no sweating glands. All hot-blooded animals use various strategies to cool when they risk going into hyperthermia when their bodies heat up to the point that they may die because their brains may get damaged. The main one is the simplest one: do not go through sustained efforts for a long time. But that, as you may imagine, is difficult to do when you have a predator running after you. Then, the choice is between stopping to cool down, or fainting because of hyperthermia. In both cases, the creature gets eaten, but that’s how planetary ecosystems work all over the galaxy.

As you may imagine, the problem of hyperthermia is especially serious in some specific environments. You read in your training materials that the naked apes are the descendants of very ancient apes which left their traditional forests to move to a new kind of environment. It was during the period that ape scientists call “Neogene” that a new ecosystem appeared, it is called “savanna,” and it is formed mainly of grassy plains. It is dry most of the time, and it offers little or no shelter against the sun. Hyperthermia is always a risk for animals living in a savanna. And that’s exactly where the ancestors of the naked apes expanded a few million years ago. I am projecting for you an image made by ape scientists of how these ancestors could have looked like. They were called “australopithecines;” they lived in equatorial regions, very hot and dry. This species does not exist anymore, but it is possible that they were hairy, at least in part, as shown in this figure. Or they may have been already naked. We cannot know that; hair is not preserved in the fossil record.

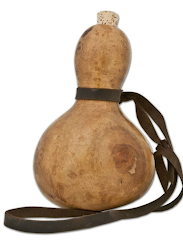

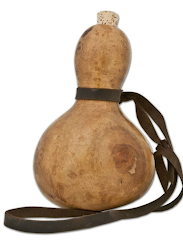

So, the early hominins had this dilemma: either they stayed with the hair of a forest ape, and that would mean dying of hyperthermia in the savanna, or they shed their hair and increased the number of sweating glands, but that could mean dying of dehydration. You know that natural selection favored the second strategy. And the fight against the dehydration danger was carried out in a truly clever way. Let me show this image; this curious object.

-- Meuianga, what is that? We said we were baffled, but now we are even more baffled.

-- What in the galaxy would that thing be?

-- Is it an artifact? Is it a plant? What is it?

Don’t be baffled, cadets. You have to learn about the infinite variety of the planets you’ll visit in your career as Starfleet officers. This is a plant and an artifact. It is also the most deadly weapon that the naked apes ever developed.

Ah… cadet Viiskewa'ite, your question shows that you are sharp-minded. Indeed, what we do in our studies is to seek the explanation that looks like the most likely one, but we can never be sure. This is a field that we might call “reverse engineering evolution.” Neither the ape scientists nor we can have a record of all the generations that went on, one after the other, to create the variety of species of the ecosystem of planet Earth. The only thing we know is that if something exists, there has to be a reason for it to exist. And suppose we frame this idea within the idea of evolution by natural selection; then, we must conclude that what we observe is the result of the survival of those individual creatures which had it over those which didn’t. But some details will always escape us, and about others, we will never be completely sure. But allow me, cadets, to tell you that I do believe that the story I told you is truly the most likely one and perhaps the only one that can explain to us why these interesting apes are naked and why they are what they are and behave the way they behave. Let me tell you a story that, I believe, will convince you.

You read in your training material of these huge mammals that populate Earth’s oceans -- they are called “whales.” Now, one whale of medium size may be hundreds of times larger than a naked ape. Even thousands of times. Yet, the apes hunt whales. They almost exterminated all of them.

-- Really? then they are good swimmers, these apes, after all!

-- But they can’t sweat underwater, Meuianga. How can they do that?

Good observations, cadets. They can indeed swim, but it is also true that their sweat glands would not help them while swimming. That’s not how they can catch those whales. They don’t swim after them.

-- But, Meuianga, we are confused. If they don’t swim, how can they reach the whales underwater?

Nothing to be confused about, cadets. Don’t forget that whales are mammals. Do you see my point?

-- Ah… Meiuanga, we see it. We see it.

-- If those whales are mammals, they must have lungs.

-- And lungs must be used to breathe air.

-- Yes, lungs won’t work underwater.

Exactly, cadets. It means that whales must get out of the water as much as they need to breathe air. Then, they can swim back below the water. But, while they breathe, the naked apes can reach them with one of their floating vessels. They call them boats.

Now, let me go back to about two hundred Earth years. I was young, I was just starting to study this planet, and my old master Fiyei Te Äyi Tipxtäa'ite was leaving Earth to take an assignment on a system located in the Magellan Cloud. So, I was left almost alone to study Earth and its many creatures. You can say that I was fascinated. Really. A lot. And I befriended some naked apes. I already told you about this ape scientist, Charles Darwin. I have to say that as a scientist, he was almost as good as the honorable Tipxtäa'ite, who had taught me the rudiments of the science of Earth’s ecosystem. But I also met another Earthling -- not a scientist, but a smart creature nevertheless. His name was Herman Melville. He was what the naked apes call a “novelist” -- let me not go into what that means, but it has something to do with the “legends” I was telling you about before. In any case, this Melville wrote a hugely interesting treatise on whales -- actually a form of legend. He was a fine observer of nature. I believe he was the first naked ape who seriously wondered what a marine mammal such as a whale could think. And how a whale could see the world. Amazing, considering the limits of how these apes think: they tend to consider themselves the only thinking creature in the universe.

Anyway, I read this text written by Melville -- it had a title, it was “Moby Dick.” I must say that I didn’t understand so much about it. Melville was very learned, and he knew a lot of things, but I was still learning about the legends that the naked apes have in their minds, so it was hard for me to understand his text. So, I went to visit him. He was a little old at that time, but still he understood who I was and what I wanted. We can get on nicely with the apes, although sometimes we have to drug them a little. Apparently, our green scales upset them. But Melville was not upset about me, and he told me a lot of things about how the naked apes hunt whales. Which, again, were rather mysterious to me. He was a male ape of remarkable culture, but, as I said, not a scientist.

In any case, at some moment, I had a flash of understanding: the mystery of the nakedness of the apes was solved. It was, indeed, the way I told you. They use their turbocharged metabolic system to hunt other creatures, even much larger ones. And with this high rate metabolism, they can wear them down, and then kill them. It appeared clear to me when I understood how they hunted whales. I saw them doing that. I used one of our flying saucers to observe how the apes hunted whales.

-- “Flying saucer?”

-- Meuianga, what would that be?

-- Meuianga, we don’t understand. What do you mean?

Oh…. sorry, cadets. I used a term from the apes’ language. That’s the way they call our atmoships when they can see one. It is when we don’t use a mirage mantle -- that slows down the atmoship too much. So, when the apes see it, they use this term because the ship’s round shape reminds them of the shape of one of their food supports. Not that they understand what they are, but they are fascinated by them, and some of them even guessed that right. But their atmoships are much slower than ours, so we don’t risk having to interact with them. Anyway. I boarded one of our atmoships and watched the hunt from above. Fascinating, cadets, absolutely fascinating. Here is a picture I took. Look at how small the ape boats are in comparison to the whale

I have more records from the hunts I witnessed, one of these sessions I’ll show them to you. But let me just tell you the main points of how whales are hunted. At that time, the naked apes had sea vessels pushed by winds -- they didn’t use engines; they developed them much later. Anyway, these ships, they called them “sailing ships,” worked well enough for what the apes needed. Now, a sailing ship can be as big as a whale, even bigger, but it cannot be maneuvered fast enough to run after a whale. So, they use much smaller boats. They have sails, too, but when they get close to the whale, they use long poles to push the boat through the water. They call those poles “oars,” and using them is called “rowing.”

When I saw one of those boats for the first time, I thought it was completely impossible that they could hunt whales using those small things. There are only six apes in each boat, and they have to run after a beast that weighs ten times all of them, including the boats. And yet, you should have seen them. They row, they row, they row, they never stop chasing the whale. Look, I’ll read for you a text that Melville wrote about that. These are words supposed to be said by the captain of the small boat (yes, even ape ships have captains!)

‘Pull, pull, my fine hearts-alive; pull, my children; pull, my little ones,’ drawlingly and soothingly sighed Stubb to his crew, some of whom still showed signs of uneasiness. ‘Why don’t you break your backbones, my boys? What is it you stare at? Those chaps in yonder boat? Tut! They are only five more hands come to help us—never mind from where— the more the merrier. Pull, then, do pull; never mind the brimstone—devils are good fellows enough. So, so; there you are now; that’s the stroke for a thousand pounds; that’s the stroke to sweep the stakes! Hurrah for the gold cup of sperm oil, my heroes! Three cheers, men—all hearts alive! Easy, easy; don’t be in a hurry—don’t be in a hurry. Why don’t you snap your oars, you rascals? Bite something, you dogs! So, so, so, then:—softly, softly! That’s it—that’s it! long and strong. Give way there, give way! The devil fetch ye, ye ragamuffin rapscallions; ye are all asleep. Stop snoring, ye sleepers, and pull. Pull, will ye? pull, can’t ye? pull, won’t ye? Why in the name of gudgeons and ginger-cakes don’t ye pull?—pull and break something! pull, and start your eyes out! Here!’ whipping out the sharp knife from his girdle; ‘every mother’s son of ye draw his knife, and pull with the blade between his teeth. That’s it—that’s it. Now ye do something; that looks like it, my steel-bits. Start her—start her, my silver-spoons! Start her, marling-spikes!’

I am not sure I understand everything that’s being said in this text -- some expressions remained mysterious to me even when Melville tried to explain them to me. But never mind that. The point of this text is how it flows. You can almost feel the effort of the rowing apes. The captain, an ape named “Stubb,” is encouraging them to row; he says, “pull, pull, pull.” He calls them all sorts of funny names. Can you understand the meaning of “ragamuffin rapscallions?” I can’t. I ran these terms through our best AI programs, and they were confused, just like me. It is an insult and, at the same time, it is not an insult. In some strange ape way, it is supposed to encourage them. And don’t forget that there are just six apes in the boat. This little boat, running as fast as it can, it has to catch an enormous whale. And they can! The incredible thing is that they can. The whale tries to run away, but it has to surface every once in a while to breathe. And when the apes see the spray of the whale breath, they row in that direction. And the whale cannot run away. No matter how it tries, the boat follows it. Eventually, the whale is exhausted enough that the boat can get close. And then the apes start shooting sharp metal points at the beast - they call them “harpoons.” So, the whale starts losing blood, and it gets more and more exhausted. And finally, it goes into hyperthermia. Its blood becomes hot, its brain ceases to work. The beast floats, inert, bleeding, waiting for the apes to finish it with a long metal needle. They call it a “lance.”

-- Amazing, Meuianga. We are honored to have received such training from you.

-- Yes, Meuianga, we are all clicking our scales in your honor.

-- It was a great lesson. We’ll remember it for a long time

-- And we can’t wait to learn more about these naked apes!

And I am honored to have had such smart pupils, cadets. Thank you so much for your interest. About learning more, yes, you won’t believe how much there is still to be learned about these apes. We’ll restart soon. In the meantime, I am asking Captain Pxaymeflae'itan to beam me down to Earth again.

Of course, Meuianga Mera. I am also thanking you for your wonderful lesson. Should I beam you back to Antarctica, then?

No, Captain. I think I deserve a little relax. Would you beam me to one of those islands… those that the Apes call “Hawai’i”?

I can do that. I am sure you can enjoy that, Meuianga Mera. One day, you should explain to me what is that thing called "Bloody Mary" that you seem to love so much.

Lectures by Meuianga Mera