Featured Post

Holobionts: a new Paradigm to Understand the Role of Humankind in the Ecosystem

You are a holobiont, I am a holobiont, we are all holobionts. "Holobiont" means, literally, "whole living creature." It ...

Thursday, March 2, 2023

Forests and History: A Tale of the Great Earth Holobiont

Sunday, February 19, 2023

In memory of an old giant: the great oak of Fiesole.

The Great Oak of Fiesole, in Tuscany, grew close to where I lived for most of my life. I can't say how old it may have been, surely at least one century, perhaps more. In the picture (of a few years ago), you see how large it was in comparison with Cristina.

The oak was a feature of my world. I have been living in that area for nearly 50 years, and I don't remember when exactly I discovered this giant tree, but I can tell you that it was the target of many attempts of mine to speak with trees. I must admit that, despite my efforts, the Great Oak never spoke back to me in intelligible words. But I often had the sensation that we were communicating with each other in ways that didn't imply words.

I moved to a different location in 2019, on the other side of the town. But I went back a few times to visit the Great Oak. Unfortunately, last summer, I discovered that it was no more. Still standing, but dead.

Thursday, February 16, 2023

Trees Come from Air

Richard Feynman, 1983. He didn't have the concept of "holobiont" -- but in this clip, he shows that he clearly understood the metabolism of the biosphere. (the part about trees starts at 3:50).

Monday, February 13, 2023

On the Happiness of Underwater Holobionts

Zhuangzi and Huizi were strolling (you 遊) on the dam of the Hao River.

Zhuangzi said, “How these minnows jump out of the water and play about (you 游) at their ease (cong rong 從容)! This is fish being happy (le 樂)! ”Huizi said: “You, sir, are not a fish, how (an 安) do you know (zhi 知) what the happiness of fish is?”

Zhuangzi replied: “You, sir, are not me, how (an 安) do you know (zhi 知) that I do not know (bu zhi 不知) what the happiness of fish is?”

Huizi said: “I am not you, sir, so I inherently don’t know you; but you, sir, are inherently no fish, and that you don’t know (bu zhi 不知) what the happiness of fish is, is [now] fully [established].”

Zhuangzi replied: “Let’s return to the roots [of this conversation]. By asking “how (an 安) do you know (zhi 知) the happiness of fish,” you already knew (zhi 知) that I know (zhi 知) it, and yet you asked me; I know (zhi 知) it by standing overlooking the Hao River.”

(Zh. 17. Trans. Meyer, “Truth Claim”, 335, modified.)

Sunday, February 5, 2023

Breathing Trouble: New research shows the risks from prolonged use of face masks

The risks appear to be especially pronounced for young people. As part of a team of scientists, one of the authors of this article conducted a randomized study of the effects of masking on healthy school aged children in Germany. The results of this research, published in September 2022 in the peer reviewed journal Environmental Research, concluded that wearing masks raised the carbon dioxide (CO₂) “content in inhaled air quickly to a very high level in healthy children in a seated resting position that might be hazardous to children’s health.”

These results should not have come as a surprise. It has long been suspected that mask-wearing poses risks. In Germany, for instance, workers required to wear an N95/FFP2 respirator must get a certificate verifying their ability to do so, and even with said certificate, those workers are mandated to take a 30-minute break every 90 minutes.

Only in the 19th century, with the development of germ theory, did masks begin being used as health devices. Then in the early 20th century, masks gained a foothold in hospitals, usually worn by doctors and nurses. The “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918-20 was perhaps the first case of masks being worn by the general public, but we only have scattered photographic pictures of masked people and don’t know how frequently they were worn.

During the 20th century, most scientists believed that masks could be useful only in hospitals for the prevention of surgical wound infections in high-risk cases. Still in 2010, a study overseen by Dr. Ben Cowling, a professor of public health at the University of Hong Kong, found weak evidence, if any, that masks could be a useful tool for stopping airborne infections.

There’s thus every reason to believe that, in March 2020, when Dr. Anthony Fauci discouraged Americans from wearing masks, he was simply stating a widely accepted medical orthodoxy. Population-level mandatory face masking had never been attempted before, and there was no reliable data proving its effectiveness, nor data detailing its adverse effects. It was reasonable to be cautious before recommending such a drastic and untested solution.

Yet this attitude rapidly changed, most likely because of political factors. It is not that politicians were directly meddling with medicine; more likely, they simply wanted to be seen as “doing something.” Masks offered visible evidence that the leaders were acting against the pandemic, and so masks appeared to be a good idea. The medical authorities rapidly sensed what was expected of them—back up the politicos—and they complied, even in the absence of data supporting the decision.

After more than two years of widespread masking, which remained mandatory for young school children long after it was abandoned by the politicians who imposed such measures, we are starting to see more data. But many studies are of poor quality, performed on small populations, based on questionable assumptions, using debatable statistical methods, and often using air that is unnaturally saturated with viral particles.

Some studies do indicate that, at least in some conditions, masks can slow down the diffusion of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Masks are not, however, a miracle device that can fully stop the virus. As doctors were saying in early 2020 before the public health establishment reversed its position on the issue, aerosol particles carrying the coronavirus are simply too small to be completely stopped by the filtering tissue of standard masks, and even less so because of how often masks are worn incorrectly.

It is our view, then, after considering the available scholarship, that we cannot establish any clear and conclusive benefits to widespread masking.

Can we establish the presence of any harmful effects? Here, we enter a complicated field of study, as it is difficult to determine the adverse effect of masks on wearers. Such a gap in knowledge is part of a pattern: In the history of medicine, there have been some glaring failures in detecting adverse effects. You may remember, for instance, the story of thalidomide, a drug marketed in the 1950s as a sedative, that was later found to cause birth defects. It had not been properly tested on pregnant women.

One problem with determining adverse effects is that you can’t knowingly expose people to something that you suspect causes serious harm, not even in the name of science. The Nuremberg Code, a set of international ethical principles created after the Doctors Trial for Nazi medical war crimes, prohibits experimentation on human subjects without their explicit consent. Another problem is that adverse effects are often delayed in time. Think of the health effects of cigarettes. Nobody ever died because they smoked one cigarette. After several decades of studies, however, it was possible to determine that if you are a smoker your life expectancy is reduced by a significant number of years.

Just like smoking a single cigarette never killed anyone, wearing a face mask for a few hours or a few days does not cause irreversible damage either. But the immediate short-term physiological effects are detectable: A recent study led by Pritam Sukul, senior medical scientist at the University Medicine Rostock in Germany, found masks to cause hypercarbia (high concentration of CO₂ in the blood), arterial oxygen decline, blood pressure fluctuations, and concomitant physiological and metabolic effects. On a time scale of weeks or months, these effects appear to be reversible. But how can we know what can happen to people who wear masks for several hours a day for several years? Will we have to wait for decades before concluding that masks are bad for people’s health, as was the case with cigarettes?

Not necessarily, for we are able to assess face masks in terms of the air quality breathed by the wearers. One important parameter for air quality is CO₂ concentration. Over the years, a lot of data has been accumulated in this field from miners, astronauts, submariners, and other people exposed to high concentrations of CO₂. Measurable negative effects on mental alertness already occur at CO₂ concentrations over 600 parts per million (ppm), which is only slightly higher than the average concentration in open air (a little more than 400 ppm). Values higher than 1,000-2,000 ppm are not recommended for living spaces, especially for children and pregnant women. 5,000 ppm is the commonly accepted limit in working environments or in submarines and spaceships. Concentrations in the range of 10,000-20,000 ppm are not immediately life-threatening but can only be withstood for short periods. Even higher concentrations may lead to loss of consciousness and death.

So what kind of CO₂ concentration are people exposed to when they wear a face mask? Measuring the concentration of CO₂ inside the small volume of a face mask while it is being used poses practical problems, and there are no standardised methods and procedures to evaluate this. Nevertheless, during the past few years, several papers dealing with this subject were published.

Some of these papers were criticised, but often baselessly. For instance, some fact checkers claimed that the same amount of CO₂ could be found without face masks in exhaled breath. This is true, but trivial. The studies mentioned above measured the amount of CO₂ in the inhaled air under face masks; the fact checkers measured the air exhaled. Other fact checkers provided a priori statements by “experts,” including a sports reporter.

Meanwhile, studies that rely on robust capnographic methods that calculate inhaled CO₂ levels from the end-tidal volume of CO₂ under strictly controlled conditions have corroborated our findings about elevated CO₂ levels in masks. In short, there is strong evidence that people wearing face masks, especially the FFP2/N95 type, breathe a concentration of carbon dioxide several times higher than the recommended concentration limits, in the range of over 5,000 ppm and often over 10,000 ppm. In other words, masks may multiply the external CO₂ concentration by a factor of 10, if not more.

Individuals wearing a tight, N95-style face mask are thus breathing air of comparable quality to the air in spacecrafts and submarines. Astronauts and submariners, though, are well trained and in peak physical condition; masks, meanwhile, are often worn by the elderly, the young, and people affected by chronic pathologies. A recent study of more than 20,000 German children who wore masks for an average of more than four hours per day showed that 68% of them reported these kinds of problems.

There are additional risks associated with face masks that should be considered, such as psychological effects and infections from pathogens accumulated in the mask tissue, but we believe that the increased concentrations of CO₂ breathed by mask-wearers is a clear and demonstrated adverse effect that should be known and considered when deciding policies. In short, face masks are not harmless.

Wearing a face mask is not a purely symbolic gesture like wearing a lapel pin or waving a flag, as some people have come to believe. It is not simply an expression of social solidarity, belief in science, or support for health care workers. It can have important adverse effects on health—especially in the case of N95s—and, at the very minimum, citizens should be alerted to the downsides of masking before they make up their minds on the issue. Face masks should be mandated only in special circumstances, and ordinary citizens should wear them only when there is a real and evident risk of infection.

Thursday, February 2, 2023

Those Pesky Savanna Monkeys: The New Large Igneous Province

This is the second part of a short series dedicated to the "Savanna Monkeys," aka "homo sapiens". In the previous post, I described how they evolved and how they changed Earth's ecosystem in the process. Here, we take a peek at the future. The monkeys could really do a lot of damage.

The giant volcanic eruptions called LIPs tend to appear on our planet at intervals of the order of tens or hundreds of million years. They are huge events that cause the melting of the surface of entire continents. The results are devastating: of course, everything organic on the path of the growing lava mass is destroyed and sterilized, but the planet-wide effect of the eruption is even more destructive. LIPs are believed to warm coal beds at sufficiently high temperatures that they catch fire. These enormous fires draw down oxygen from the atmosphere, turning it into CO2. The result is an intense global warming, accompanied by anoxia. In the case of the largest of these events, the End-Permian extinction of some 250 million years ago, the whole biosphere seriously risked being sterilized. Fortunately, it recovered and we are still here, but it was a close call.

LIPs are believed to be the result of internal movements of the Earth's core. For some reason, giant lava plumes tend to develop and move toward the surface. It is the same mechanism that generates volcanoes, just on a much larger scale. From what we know, LIPs are unpredictable, although they may be correlated to a "blanketing effect" generated by the dance of the continents on Earth's surface. When the continents are clustered together, they tend to warm the mantle below, and that may be the origin of the plume that creates the LIP

Of course, if a LIP were to take place nowadays, the results would be a little catastrophic -- possibly more catastrophic than the fantasy of Hollywood's movie makers can imagine. They have thrown all sorts of disasters at hapless humans, from tsunamis to entire asteroids. But imagine the whole North American continent becoming a red-hot lava basin, well, that's truly catastrophic!

Fortunately, LIPs are slow geological processes and even if there is one more of these events in our future, it won't happen on the time scale of human lifetimes. But that doesn't mean that humans, those pesky Savanna Monkeys, can't do their best to create something similar. And, yes, they are engaged in the remarkable feat of creating a LIP-equivalent by burning huge amounts of organic ("fossil") carbon that had sedimented underground over tens or hundreds of millions of years of biological activity. It is remarkable how rapid the monkey LIP has been. Geological LIPs typically span millions of years. The monkey LIP went through its cycle over a few hundred years: we see it developing right now. It will be over when the concentration of fossil carbon stored in the crust will become too low to self-sustain the combustion with atmospheric oxygen. Just like all fires, the great fire of fossil carbon will end when it runs out of fuel, probably less than a century from now. Even in such a short time, the concentration of CO2 is likely to reach, and perhaps exceed, levels never seen after the Eocene, some 50 million years ago. It is not impossible that it could reach more than 1000 parts per million.There is always the possibility that such a high carbon concentration in the atmosphere will push Earth over the edge of stability and kill Gaia by overheating the planet. But that's not a very interesting scenario: we all die and that's it. So, let's examine the possibility that the biosphere will survive the great carbon pulse generated by the savanna monkeys. What's going to happen?

The savanna monkeys themselves are likely to be the first victims of the CO2 pulse that they generated. Without the fossil fuels they have come to rely on, their numbers are going to decline very rapidly. From the incredible number of 8 billion individuals, that they recently reached, they are going to return to levels typical of their early savanna ancestors: maybe just a few tens of thousands. Quite possibly, they'll go extinct. In any case, they will hardly be able to keep their habit of razing down entire forests. Without monkeys engaged in the cutting business and with high concentrations of CO2, forests are advantaged over savannas, and they are likely to recolonize the land, and we are going to see again a lush, forested planet (arboreal monkeys will probably survive and thrive). Nevertheless, savannas will not disappear. They are part of the ecosystem, and new megaherbivores feeding on them will evolve in a few hundred thousand years.

Over deep time, the great cycle of warming and cooling may restart after the monkey LIP is over, just as it did for the "natural" geological LIPs. In a few million years, Earth may be seeing a new cooling cycle that will lead again to a Pleistocene-like series of ice ages. At that point, new savanna monkeys may evolve. They may restart their habit of exterminating the megafauna, burning forests and building things in stone. But they won't have the same abundance of fossil fuel that the monkeys called "Homo sapiens" found when they emerged into the savannas. So, their impact on the ecosystem will be smaller, and they won't be able to create a new monkey-LIP.

And then what? In deep time, the destiny of Earth is determined by the slowly increasing solar irradiation that is going, eventually, to eliminate all the oxygen from the atmosphere and sterilize the biosphere, maybe in less than a billion years from now. So, we may be seeing more cycles of warming and cooling before Earth's ecosystem collapses. At that point, there will be no more forests, no more animals, and only single-celled life may persist. It has to be. Gaia, poor lady, is doing what she can to keep the biosphere alive, but she is not all-powerful. And not immortal, either.

Nevertheless, the future is always full of surprises, and you should never underestimate how clever and resourceful Gaia is. Think of how she reacted to the CO2 starvation of the past few tens of millions of years. She came up with not just one, but two brand-new photosynthesis mechanisms designed to operate at low CO2 concentrations: the C4 mechanism typical of grasses, and another one called crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). To say nothing about how the fungal-plant symbiosis in the rhizosphere has been evolving with new tricks and new mechanisms. You can't imagine what the old lady may concoct in her garage together with her Elf scientists (those who also work part-time for Santa Claus).

Now, what if Gaia invents something even more radical in terms of photosynthesis? One possibility would be for trees to adopt the C4 mechanism and create new forests that would be more resilient against low CO2 concentrations. But we may think of even more radical innovations. How about a light fixation pathway that doesn't just work with less CO2, but that doesn't even need CO2? That would be nearly miraculous but, remarkably, that pathway exists. And it has been developed exactly by those savanna monkeys who have been tinkering with -- and mainly ruining -- the ecosphere.The new photosynthetic pathway doesn't even use carbon molecules but does the trick with solid silicon (the monkeys call it "photovoltaics"). It stores solar energy as excited electrons that can be kept for a long time in the form of reduced metals or other chemical species. The creatures using this mechanism don't need carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, don't need water, and they may get along even without oxygen. What the new creatures can do is hard to imagine for us (although we may try).

In any case, Gaia is a tough lady, and she may survive much longer than we may imagine, even to a sun hot enough to torch the biosphere to cinders. Forests are Gaia's creatures, and she is benevolent and merciful (not always, though), so she may keep them with her for a long, long time. (and, who knows, she may even spare the savanna monkeys from her wrath!).

We may be savanna monkeys, but we remain awed by the majesty of forests. The image of a fantasy forest from Hayao Miyazaki's movie, "Mononoke no Hime" resonates a lot with us.

Friday, January 27, 2023

Gaia on the Move: the Rise of the Savanna Monkeys

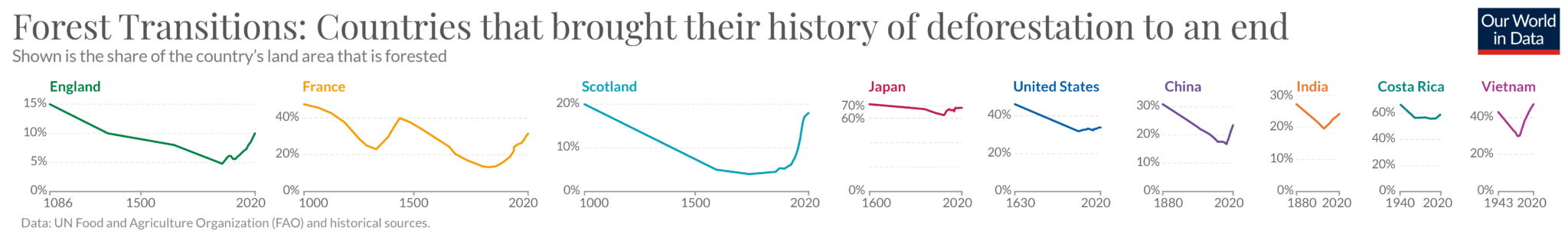

This text had already been published as an appendix to a longer post on the evolution of forests. It is republished here as a stand-alone post on the role of humans in the evolution of the world's forests (link to the image above)

Primates are arboreal creatures that evolved in the warm environment of the Eocene forests. They used tree branches as a refuge, and they could adapt to various kinds of food. Modern primates do not shy from hunting other species, maybe even ancient primates did the same. From the viewpoint of these ancient primates, the shrinking of the area occupied by tropical forests that started with the "Grande Coupure," some 30 million years ago, was a disaster. They were not equipped to live in savannas: they were slow on the ground: an easy lunch for the powerful predators of the time. Primates also never colonized the northern taiga. Most likely, it was not because they couldn't live in cold environments (some modern monkeys can do that), but because they couldn't cross the "mammoth steppe" that separated the Tropical forests from the Northern forests. If some of them tried, the local carnivores made sure that they didn't succeed. So, "boreal monkeys" do not exist (actually, there is one, shown in the picture, but it is not exactly a monkey!).

Eventually, monkeys were forced to move into the savanna. During the Pleistocene, about 4 million years ago, the Australopithecines appeared in Africa, (image source). We may call them the first "savanna monkeys." In parallel, perhaps a little later, another kind of savanna monkey, the baboon, also evolved in Africa. In the beginning, australopithecines and baboons were probably practicing similar living techniques, but in time they developed into very different species. The baboons still exist today as a rugged and adaptable species that, however, never developed the special characteristics of australopithecines that turned them into humans. The first creatures that we classify as belonging to the genus Homo, the homo habilis, appeared some 2.8 million years ago. They were also savanna dwellers.This branch of savanna monkeys won the game of survival by means of a series of evolutionary innovations. They increased their body size for better defense, they developed an erect stance to have a longer field of view, they super-charged their metabolism by getting rid of their body hair and using profuse sweating for cooling, they developed complex languages to create social groups for defense against predators, and they learned how to make stone tools adaptable to different situations. Finally, they developed a tool that no animal on Earth had mastered before: fire. Over a few hundred thousand years, they spread all over the world from their initial base in a small area of Central Africa. The savanna monkeys, now called "Homo sapiens," were a stunning evolutionary success. The consequences on the ecosystem were enormous.

First, the savanna monkeys exterminated most of the megafauna. The only large mammals that survived the onslaught were those living in Africa, perhaps because they evolved together with the australopithecines and developed specific defense techniques. For instance, the large ears of the African elephant are a cooling system destined to make elephants able to cope with the incredible stamina of human hunters. But in Eurasia, North America, and Australia, the arrival of the newcomers was so fast and so unexpected that most of the large animals were wiped out.

By eliminating the megaherbivores, the monkeys had, theoretically, given a hand to the competitors of grass, forests, which now had an easier time encroaching on grassland without seeing their saplings trampled. But the savanna monkeys had also taken the role of megaherbivores. They used fires with great efficiency to clear forests to make space for the game they hunted. Later, as they developed metallurgy, the monkeys were able to cut down entire forests to make space for the cultivation of the grass species that they had domesticated meanwhile: wheat, rice, maize, oath, and many others.

But the savanna monkeys were not necessarily enemies of the forests. In parallel to agriculture, they also managed entire forests as food sources. The story of the chestnut forests of North America is nearly forgotten today but, about one century ago, the forests of the region were largely formed of chestnut trees planted by Native Americans as a source of food (image source). By the start of the 20th century, the chestnut forest was devastated by the "chestnut blight," a fungal disease that came from China. It is said that some 3-4 billion chestnut trees were destroyed and, now, the chestnut forest doesn't exist anymore. The American chestnut forest is not the only example of a forest managed, or even created, by humans. Even the Amazon rainforest, sometimes considered an example of a "natural" forest, shows evidence of having been managed by the Amazonian Natives in the past as a source of food and other products.The most important action of the monkeys was their habit of burning sedimented carbon species that had been removed from the ecosphere long before. The monkeys call these carbon species "fossil fuels" and they have been going on an incredible burning bonanza using the energy stored in this ancient carbon without the need of going through the need of the slow and laborious photosynthesis process. In so doing, they raised the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere to levels that had not been seen for tens of millions of years before. That was welcome food for the trees, which are now rebounding from their former distressful situation during the Pleistocene, reconquering some of the lands they had lost to grass. In the North of Eurasia, the Taiga is expanding and gradually eliminating the old mammoth steppe. Areas that today are deserts are likely to become green. We are already seeing the trend in the Sahara desert.

What the savanna monkeys could do was probably a surprise for Gaia herself, who must be now scratching her head and wondering what has happened to her beloved Earth. And what's going to happen, now? There are several possibilities, including a cataclysmic extinction of most vertebrates, or perhaps all of them. Or, perhaps, a new burst of evolution could replace them with completely new life forms. What we can say is that evolution is turbo-charged in this phase of the existence of planet Earth. Changes will be many and very rapid. Not necessarily pleasant for the existing species but, as always, Gaia knows best.