The Amanita Muscaria, perhaps the most beautiful mushroom in the world. Said to be poisonous, some say it is edible. It can also have hallucinogenic effects. In any case, the bright red color is a signal directed to animals that, basically, says, "eat me." And the resulting hallucinations may well be a further reason for animals (humans in particular) to seek for it. This bright livery and the mental effects of the fungus may be the origin of the myth of a fat man driving a sled pulled by reindeer and dressed in a liver that's exactly of the same colors. But, apart from myth creation, fungi can be the basis of a number of interesting advanced technologies to recycle waste and produce food. (note: in this text, I often use the concept of "holobiont" that may not be familiar to most people. To know more about it, see the blog "The Proud Holobionts")

Fungi as holobionts

Fungi are the quintessential holobionts. Neither plants nor animals, they are a world apart from us. They lack the capability of photosynthesis and so they cannot live except as associating themselves to plant roots (they are called "mycorrhizal") or, sometimes, as scavengers (in this case, we call them "saprophytes"). In both cases, they obtain their food from plants and, in exchange, they provide plants with a variety of services, including the all-important capability of extracting minerals from the soil and turning them into forms that plants can absorb. The relationship between plants and fungi is so strict and intricate that some plants live on fungi: they are epiparasites ("parasites of parasites"). Holobionts have many way to exist!

Fungi, plants, and animals form different "kingdoms" in the biological classification of living creatures. But the separation between fungi and animals is especially sharp. We may see fungi as the specular opposite of animals in terms of their survival strategies. Both depend on plants, but they live on opposite sides of the ground surface. Animals, like us, live mainly above ground, mushrooms underground. What we see of them is the occasional appearance of the "fruiting body," or the "mushroom," the sexual organ of the underground creature. (if you want to know the proper scientific term, it is the "epigeal" part of the creature).

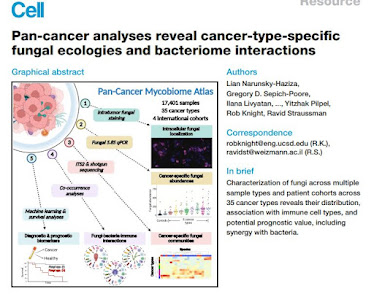

Given the different environments in which fungi and animals live, it is not surprising that the interactions between fungi and animals are usually limited. Although fungal spores pervade the air we breathe, even in towns and inside homes, we do not harbor many fungal species in our bodies. The Candida Albicans is one of the few examples: it is common in human bodies, where it is probably doing a useful job as a saprophyte, removing decayed materials. But, occasionally, the Candida may become a pathogen and do plenty of damage when something goes wrong in the complex equilibrium of the human holobiont.

Nevertheless, the above-ground manifestations of fungi are part of the human lore, and also of the human diet. But even as food, mushrooms are not so common, and they are surrounded by myths and legends: some are poisonous, some are hallucinogenic, most have no eating value, but some are considered prized food -- think of truffles!

From the viewpoint of fungi, we animals may be considered exotic and legendary creatures, often causing damage but in some cases useful to spread the spores. Truffles would not smell so good to human (and animal) noses if they didn't "want" to be dug out and eaten. The same is true for the brightly colored mushrooms that advertise themselves as good food (or, in some other cases, carrying the "do not eat me" message).

So, fungi and humans form the kind of symbiotic relationship of holobionts only occasionally. In particular, humans are not so good at cultivating fungi as food, but by far not as good as they are at cultivating plants and herding animals. To this day, mushrooms remain one of the few human foods that are mainly harvested from the wild. The capability of cultivating them is a recent skill acquired in human history. It is said that the first mushroom cultivations were developed in China during the first millennium AD. By now, several species can be cultivated, mostly of the saprophyte kind, (the Japanese "shiitake" are an example). Cultivating mycorrhizal fungi, such as truffles, is much more complicated because they live in association with a living plant, which must be provided by humans. "Truffiéres" do exist, but they are a recent development. In all cases, cultivating mushrooms is a step upward in complexity with respect to conventional agricultural techniques.

Despite the problems involved, cultivating fungi is an attractive idea for many reasons. Apart from food, the capability of saprophytes to break down materials that humans consider waste is interesting: if we can turn waste into food, we can "close the cycle" of many agricultural and industrial activities and move in the direction of the "circular economy" that is the only kind of economy that can last a long time. Can fungi be a fundamental tool for that purpose? Maybe, but we are still far away from a truly circular economy. Let me tell you something about my experience in this field.

Cultivating the mushroom holobiont: the circular farm

It was Galileo who said that "knowledge is the child of experience" (la sapienza è figliola della sperienza). So, in order to learn something about fungi and their cultivation, I took a two-day full-immersion class in mushroom cultivation organized by a company engaged in that field. Amazing: there were so many things I didn't know about that, and so many tricks I hadn't even imagined. I don't think I'll ever become a professional mushroom grower, but it was surely an enriching experience.

First, let me tell you a few things about the "Circular Farm" company created by Antonio Di Giovanni, a spinoff of the "Funghi Espresso" company. One of the many good things that can be said about the company is that it is a real company, one that's making a product and selling it. I say this because, over a career of working with startup companies, I arrived at the conclusion that most of them are scams. They are there to cash in government grants and gullible investors. When they have made enough money, they close shop and good riddance. That's not the case with the Circular Farm company.The objective of the company, as its name says, is to "close the circle" of the resources it uses -- recycling what others call waste. So, the cultivation of mushrooms is made mainly on coffee ground waste recovered from local coffee shops. The process is remarkably efficient: about 20% of the waste is transformed into edible mushrooms. What is left is composted and it could be another sellable product, were it not for the Italian bureaucracy that forbids selling it, or even giving it away for free. But it is not a pollutant, so it can be used to grow the vegetable garden of the company.

The company is also engaged in developing more products, different kinds of fungi on different substrates, applications of fungi other than food, and other agricultural technologies according to the concept of "urban farm." After all, the idea of cultivating something inside towns is not new: our ancestors often had vegetable gardens, and they derived a substantial fraction of their food supply from them. If it worked for them, it can work for us, too!

Fungi as a tool to attain a circular economy: is it possible on a large scale?

The idea of recycling coffee ground waste appears to be a success story. The Circular Farm company can do that, and it is not the only one. In the UK, the Bio-bean company does the same, although on a larger scale and its products are different -- including, for instance, "coffee logs" to be used as fuel for wood stoves. The question is, what can these successes teach us about the more general problem of waste recycling?

One good thing about the idea of recycling coffee waste is that it is a commercial activity. That is, it is a real way to make profits while, at the same time, doing something useful for society; in this case getting rid of some waste. But expanding the idea to a much larger scale, well, it is not so easy.

Waste is a peculiar entity. For one thing, it has a "negative price," in the sense that people are willing (or, more often, are forced) to pay to get rid of it. This generates the problem that would-be recyclers find themselves in competition with waste management companies, whose business is not recycling, but disposal. Since the public is forced by law to pay, these companies have an unfair advantage and they tend to use all their lobbying power to make the state enact laws that make life difficult for recyclers. In some particular cases, the business of waste disposal is so lucrative and exclusive that you risk being sent to sleep with the fishes if you become a nuisance. If you work in this field, you surely have plenty of horror stories to tell. I do, too, but let me skip this subject, here.

Another problem, and maybe the most important one, is that if something is classified as waste, it means that it is just that: waste. It means that people don't know what to do with it and just want to get rid of it. So, how come you think you can do something useful with it? Either you are especially clever or you are willing to work on the cheap side of the economy. In the latter case, you must accept to work for low profits, a strategy also known as the "church mouse" strategy."

Most of the recycling done worldwide today is performed by people who live on the edge of survival. You may have seen pictures of the people who live by scavenging landfill in places such as India or Africa. They are so poor that for them even the very modest profits made from the things that other people throw away help them to survive. But you don't need to think in terms of exotic places. You know that you can find plenty of edible food in the waste bins of your local fast food joint. Surely, it is not as good as the food you buy at the counter, but the people called "binners" rely on that food to survive. They are, by all means, good recyclers. Interestingly, though, in many Western countries "binning" is forbidden and sanctioned by law. This illustrates both the problems I was describing: the powers that be do not want you to recycle, and what you recycle is of lower quality than the original product. This is called "downcycling" and it affects most kinds of recycling, not just food found in waste bins. Recycled plastic, for instance, is a poor material in all respects, while recycled paper is good for toilet paper and little else.

Instead, the approach of the "Circular Farm" on recycling coffee waste is on the other side of the waste recycling strategy: it exploits cleverness. Indeed, they are performing a remarkable feat: transforming something that nobody wants into relatively high-priced goods, edible mushrooms. But can it be expanded? In part, yes. Fungi are nearly miraculous creatures, and they can do things that no other living creature can do. Just think of the possibility of using the chitin that fungi produce (plants don't produce it). Chitin is a solid polymer, typically used in nature by insects for their exoskeleton. Chitin could be grown by fungi inside molds and replace plastic, with the advantage that chitin is a natural substance that can be easily degraded by bacteria. Fungi might also be able to degrade plastic directly, but we are not there yet.

Overall, we are just starting to explore the many possibilities of biotechnology in many fields. It could do many useful things (and many horrible ones, bioweapons, for instance). Perhaps the most interesting possibility is to reduce the impact of agriculture on the ecosystem. This is a point that's scarcely recognized, but agriculture is one of the most destructive technologies ever devised by humankind. It occupies enormous areas, with the consequent destruction of the natural biota, deforestation, and the destabilization of the whole ecosystem. To say nothing about how, today, most agricultural production is made on soil that has been thoroughly destroyed by the overuse of artificial fertilizers and pesticides so that it has become sterile and inert ("as sterile as the brains of my students" as I say, but let me not harp on that). In itself, the cultivation of mushrooms can't replace agricultural products, but it is part of a revolution that includes "precision fermentation" which promises the production of food using bacteria with a much smaller environmental impact than conventional agriculture.

Concluding: The Holobiont Strategy

Modern biotechnologies give us hints of revolutionary possibilities, but we are not there yet. In quantitative terms, some ten million tons of coffee are produced every year in the world, practically all of which becomes coffee grounds waste. Now, Circular Farm recycles about 10 tons per year and, even though there are other companies engaged in the same task, the impact on global waste production is minimal. Besides, coffee grounds are not a major source of pollution. So, you see that it is a long road that we have to walk before we can use bacteria and fungi to replace conventional agriculture or even to make a serious dent in the pollution created by waste.

It looks more likely that we'll have to adapt to what we can do rather than dream about things we cannot do. A good strategy in terms of optimizing a production system is to mimic the way the natural system works: It is the "holobiont strategy." Holobionts do not accumulate capital -- they exchange what they produce immediately after they produce it. A good holobiont is a chain of creatures that cycle nutrients down from solar energy all the way to fertile soil, which then is returned to the top. Holobionts don't strive to become rich, they strive for stability. And they strive for efficiency: a good holobiont would never forbid fellow holobionts from getting their lunch from the waste bin of a restaurant. The holobiont way is to help, not to forbid. And so, one step after another, we'll arrive somewhere. Onward, fellow holobionts!

Photos of the Circular Farm Seminar