From the Blog of the Club of Rome

© Greatandaman | Dreamstime

By Ugo Bardi, member of The Club of Rome

02 May 2023 – Do forests create rain? It is a question that has been debated for a long time. We know that trees produce huge amounts of water vapor that is pumped from humidity in the ground and condensed into clouds that generate rain, but the mechanisms that govern condensation and vapor water movements are still not completely clear.

In our new paper, a group of researchers led by Anastassia Makarieva of the Theoretical Physics Division of Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute (PNPI) and the Institute for Advanced Study of the Technical University of München (TUM) highlight how evapotranspiration – the evaporation of water by trees, modifies water vapor dynamics to generate high moisture content regimes that provide the rain needed by land ecosystems. The research is a significant step forward in understanding the critical need to conserve old-growth forests to stabilise the Earth’s climate and maintain the biodiversity needed for the ecosystem to survive.

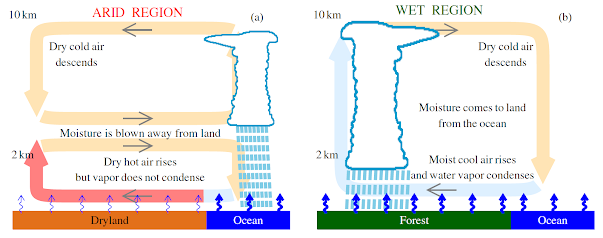

The study titled “The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence” shows that two potential moisture regimes exist: one is drier, with additional moisture decreasing atmospheric moisture import, and one is wetter, with additional moisture enhancing atmospheric moisture import. In the drier regime, that may be caused by deforestation, water vapor behaves as a passive tracer following the air flow. In the wetter regime, it modifies atmospheric dynamics and amplifies the atmospheric moisture import, creating rain.

There is still much that we need to understand about these mechanisms, but we are starting to understand how forests and the atmosphere form a system of connected elements that affect each other. One thing is clear: forests are crucial to the stability of the Earth’s climate.

Not only do trees store carbon in a form that does not cause greenhouse warming, but they actively cool the planet, due to how moisture condensation is managed. Forests also control the water cycle on land, pumping water vapor from the oceans inland by a mechanism called the biotic pump. Old growth forests generate giant flows of water known as “flying rivers” that fertilise entire continents. Our study shows that the non-linear precipitation dependence on atmospheric moisture content has wide-ranging implications. Atmospheric water flows do not recognize international borders, meaning deforestation disrupting evapotranspiration in one region could trigger a transition to a drier regime in another.

Our results indicate that the Earth’s natural forests, in both high and low latitudes, are our common legacy of pivotal global importance, as they support the terrestrial water cycle. Their preservation should be a recognised priority for our civilisation to solve the global water crisis. Important on-going work calls for re-appraisal of the forest’s role in the global temperature regime.

The study was performed by an international research team that included scientists from North and South America, and Eastern and Western Europe.