God must be

incredibly fond of holobionts, since He created so many of them. And He

(or She) may be a holobiont as well.

It once happened, that the other members of a man

mutinied against the stomach, which they accused as the only idle,

uncontributing part the whole body, while the rest were put to hardships and

the expense of much labour to supply and minister to its appetites. The

stomach, however, merely ridiculed the silliness of the members, who appeared

not to be aware that the stomach certainly does receive the general

nourishment, but only to return it again, and redistribute it amongst the rest.

(Plutarch, “Life of Coriolanus”)

In guerrilla warfare, select the tactic of seeming to

come from the east and attacking from the west; avoid the solid, attack the

hollow; attack; withdraw; deliver a lightning blow, seek a lightning decision.

When guerrillas engage a stronger enemy, they withdraw when he advances; harass

him when he stops; strike him when he is weary; pursue him when he withdraws.

In guerilla strategy, the enemy's rear, flanks, and other vulnerable spots are

his vital points, and there he must be harassed, attacked, dispersed, exhausted

and annihilated. (Mao Zedong, 1937)

Maybe it happened to you to spend hours

waiting for a flight in a busy international airport. You are blocked there and,

after having had enough coffee to make you walk like a shuffle dancer, you have

nothing else to do but to wander aimlessly from one shop to another. Bookstores

offer something to read but, perhaps more interestingly, they give you a chance

to get hints of what other people read. A rare chance of a glimpse of other

people’s minds in our busy world.

So, what are people reading, nowadays? A

lot of magazines and books that you can find in an airport bookstore are about

the two primeval human interests: food and sex (the latter usually not so

explicitly presented as the former). Apart from that, you find plenty of

material on everyday matters: cellphones and other electronic gadgetry, cars,

travel, religion, and more. In addition, the typical international airport bookstore

has a section on how to deal with other people. They are self-help books that

claim to train you on how to manage your relationship with your coworkers, your

friends, and your family.

Evidently, many people find that dealing

with others is a difficult matter, enough that they need help and guidance. It

is a little strange, because we are all the result of at least three hundred

thousand years of evolution of the species called homo sapiens. Our

ancestors survived because they were good enough at creating and keeping relationships

with their neighbors that would help them in times of need. But, perhaps,

living in the modern society, so bewilderingly complicated, is more difficult

than living in a tribe of hunters and gatherers.

Are these books really useful? There are

good reasons to be skeptical. The books often seem to be a mishmash of this and

that, they are not quantitative, not based on solid theories, not related to

experimental evidence. The latest fad in

management theory is a book titled “Reinventing Organizations.” The

title may be interesting, but the substance of the book may be criticized. According to the author, good management has something to do with a

hierarchy of colors. Infrared is primitive and bad, while the

shade of blue called “teal.” is modern and good. Why that should be the case,

is not explained anywhere in the book. That doesn’t mean to disparage a book

that may have good points, but maybe you will agree with us that such a

classification is a little arbitrary, to say the least.

So, can we make some order in this chaos?

Maybe yes. And we can try to do that using the concepts

of “holobiont” and the related one of

“empathy.” The idea is that human societies of all kinds are the result of

evolutionary pressure and that those you find in our world exist because there

is a reason for them to exist. Just as biological holobionts are a feature of

the biosphere, there exist societal holobionts, a feature

of the human social sphere. Societal holobionts are an example of “Complex

Adaptive Systems,” (CAS) that is, systems that develop a condition of stability

called “homeostasis” and that tend to maintain it when perturbed. These

holobionts are virtual, unlike the microbes in your gut. So, we may also call

them “virtual holobionts.”

Let’s start with an example. The simplest

kind of human organization is the least organized one: the crowd (you can also

call it a “mob” or a “band”). It has no leaders, no hierarchy, no

specializations. Yet, you recognize a crowd when you see one. Perhaps the first

time when crowds were dealt with as something worth of interest was with the

book by the French author Gustave le Bon “Psychologie des Foules,

(1895) that was translated into English as « The Crowd, A study of the

Popular Mind. ». Reading it today, you would probably judge it to be a

poorly made political pamphlet. And, indeed, it had a certain success with

right wing politicians. Nevertheless, it was one of the first studies of

complex systems in sociology.

Crowds are not just a feature of human

society; equivalents exist with many animal societies. They go with different

names: storms (or flocks) of birds, schools of fish, herds of sheep, prides of

lions, and there are other examples (for instance, a bacterial mat). In any

case, they share the same characteristics: they are loosely bonded groups of

individuals who may stay together for a while and dissociate back into single

units at any time. But, as long as they exist, crowds (just like all human

organizations) are groups of people linked together.

Let’s go deeper into the matter. If a

crowd is an organization, albeit the simplest possible one, it could be

described using those “organizational charts” that purport to describe how a

company is organized. These charts are maps designed to describe the hierarchical

territory of the company. They have also been used to describe the organization

of entities such as the Sicilian Mafia and Drug Cartels. They can also map the

relationships in a band of Chimps or Bonobos.

But an organizational chart can be much

more than simply a static map that tells you whom you should see, for instance,

to organize a shipment or to order a supply of something (or, if you are a male

bonobo, where to find an available female). The chart tells us a lot on how the

organization works and also something about how it developed over time. It is

part of the field called “management science.”

A good way to interpret organizational

charts is to see them as networks. Network science is a relatively recent

development that derives from a field called “graph theory.” It is something

that deals with how points in space (called “vertices”, plural of “vertex”) are

arranged in space in terms of pairwise links with other vertices. You see an

example of a graph in the figure

You note that there are 6 vertices (also

called “nodes”), each one connected to its nearest neighbors. In this case, the

connections (“links” or “edges”) are not directional, but that may be explicit

in some kinds of graphs. It may also be possible that a node is connected to

several other nodes.

Graph theory is a branch of pure mathematics,

and it deals only with geometric arrangements. Instead, “Network theory” (or

“network science”) deals with applications of graph theory to the real world.

In this case, the nodes are real entities: people, departments, servers, combat

units, and much more. Also, the links are related to real methods of

information exchange: documents, orders, radio signals, fiber optics, and more.

Armed with this a basic knowledge, let’s

go back to the example of the crowd. The simplest crowd network we may imagine

is one formed of just three people (or bonobos). Here is the graph.

You see that each node (one member of the

group) is connected to his/her neighbors. Information flows from each node to

the closest one. There is no hierarchy: all the nodes are the same, which is

one of the characteristics of crowds/bands/flocks, etc. You can say that the

relationship between the elements of this crowd is horizontal, as

opposed to the vertical kind seen in hierarchical organizations such as companies,

armies, etc, as we’ll see later on.

We can expand the graph to describe a

system where there are more than three nodes. You see below several possible

arrangements

In the first case (a), each node is

connected only to its two nearest neighbors. It is a little like being squeezed

in the crowd in a busy subway station – if you have ever visited Tokyo, you

know what that means. In such a condition, you can only move together with the

crowd, and you don’t see anything more than your nearest neighbors.

Things may be more complicated than that

and, in the other images, you see how nodes may be connected to more nodes than

just their near neighbors. In case (b) each node is in contact with 4

neighbors. It is still a crowd, but not so dense as case (a). Case (c) shows

the possibility of long-range connections for some of the nodes. Maybe someone

in the crowd is in contact with a friend in the same crowd, but using a cell

phone. Case (d) refers to a kind of network that is called “fully connected,”

meaning that every node is connected to every other node. In the real world, it

is a rare occurrence, even though it may exist for very small networks. For

instance, the 3-nodes example seen before is a fully connected network. All

these arrangements are non-hierarchical, or “horizontal”.

All these examples are special cases

where all nodes are not only identical, but have all the same number of

connections. In most cases, this is not true and each element is connected to a

different number of nodes.

The figure illustrates the variations in

the number of connections. The left examples shows a network where every node

has 4 links. The central one is called the “small world” network. Most

connections are to the close neighbors, but some are long range. The right one

has more links, randomly arranged, but it is not fully connected.

The reason why the central diagram is

called “small world” deserves some explanation. It has to do with the distance

(in terms of number of links) between nodes. In this kind of network, it grows

proportionally to the logarithm of the number of nodes, so it is not as large

as it would be if you had to crawl every node, one after the other, to reach a

node on the other side of the circle. In a small world network, if you wanted

to contact, say, the president of the United States, it is said that you need

to go through no more than six steps, starting with a person you are in contact

with. It is not exactly like this, but it is a long story. Let’s

just say that it is a “natural” way in which networks tend to arrange

themselves.

You may say that the number of connections provide an embryonic form of hierarchy in these networks. If knowledge is power, then more connections mean more knowledge and therefore more power. This hierarchical relationship is especially evident on the Internet. A site such as, say, the CNN is defined by an URL (Uniform Resource Locator) just like any other blog or site on the web. But the CNN has a hugely larger number of connections than the average web site and there is no doubt that it has much more power in terms of pushing memes in the memesphere. But, overall, these systems remain horizontal in the sense that CNN doesn’t have the possibility to order to bloggers what to publish or not to publish in their sites (so far). Many internet “bubbles” are relatively egalitarian, although some nodes (people or groups) carry more weight than others.

These non-hierarchical networks are the

general representation of the concept of “holobiont.” The way Lynn

Margulis described holobionts was in terms of a group of individuals of

different species that moved together in the condition called “symbiosis,” a

mutual relationship that provides advantages to all the creatures engaged in

it. Holobionts imply an intricate network of relationships among the various

member of the community, but no fixed hierarchical structure although,

obviously, some members have more prestige and power than others. Margulis was

thinking of microbial communities, but we can enlarge the definition to ensembles

of animals (if you prefer the formal term, we could say “ensembles of metazoa”).

But the organizational diagrams in the form of circles could describe them

nicely.

But what is the advantage for an

individual to be part of a crowd? (or a flock, or a herd, or a pride?). Are

these individuals in a symbiotic relationship? Yes, they are, by all means. Symbiosis

is a condition of mutual help that in systems is generated by the way the

system is organized, NOT by the good will of the individuals (it would be hard

to speak of good will among bacteria, for instance). The beauty of symbiosis is

that all the creatures engaged in it strive for their own benefit but, in the

process, they manage to benefit every other creature.

Said in this form, it sounds as an extreme

version of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” still today the basis of liberalism

as a political ideology. The idea of the invisible hand has been much ridiculed

over the years (you know how many economists it takes to replace a light bulb?

None, it is done by the invisible hand!). But the idea is good if it is applied

with a grain of salt.

Ugo Bardi (yours truly) and his coworker Ilaria

Perissi discussed this issue in a paper that they titled “The Sixth Law of Stupidity,”

where we argued that the opposite of stupidity is when human beings enter in

a condition of symbiosis with other people. We also argued that stupidity is

temporary while intelligence is long term, which means that people tend to

learn from their mistakes. Even creatures not especially known for their large

brains (say, bacteria) tend to learn from their mistakes – and those who don’t

learn are eliminated by natural selection.

So, humans in a crowd are in a symbiotic

relationship even though they may not recognize that. The crowd offers a

certain refuge to its members. Maybe for humans it is not a general rule: when

you are being shelled or shot, the worst possible idea would be to form a crowd

that would attract the enemy fire. But, if you look at crowds in the animal

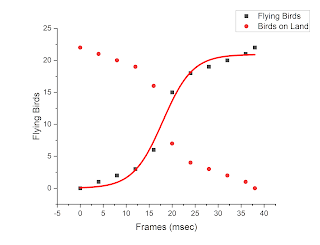

kingdom, their utility is evident. Have you ever observed the behavior of a storm

of birds? You may see them landing on a patch of grass to feed. If you get

close, one of the birds may see you, be scared, and fly off. Immediately, the nearby

birds will be alerted and fly off, too. In a moment, the whole storm will be

flying away. In this case, the crowd (the storm) offers a danger-detection

service that a single bird cannot have.

More in general, a storm/flock/herd/crowd

offers statistical protection. A predator is not interested in destroying the

whole flock, only at capturing as many individuals as it needs. So, if the

flock is large, the probability for an individual to be captured is low. Of

course, humans tend to destroy even things they don’t need, but this is part of

the 6th law of stupidity .

We have now a definition of how a

holobiont is structured according to the network theory. We may want to

represent it as a triangle and, thinking about that, there could be a relation

with the triangular symbol “the eye of God.”

And, indeed, a triangle can be seen as the icon for both a holobiont and God (or the Goddess Gaia). But let's not go into theology, this introduction should be enough to understand what a holobiont is. The next step is the concept of hierobiont, a network partly or completely structured in a hierarchical manner. But we'll see that in another post.