Once you discover the concept of "holobiont," its ramifications keep surprising you. Here is a brief discussion of how the competition among the human meta-holobionts called demes affected and was affected by the human sexual behavior.

How could it be that for a few thousand years only one human male out of about 20 females left descendants? What had happened that had removed so many males from the human gene pool? This is a story that would require an entire book to explain, but it is so fascinating that I thought I could write a quick survey, here.

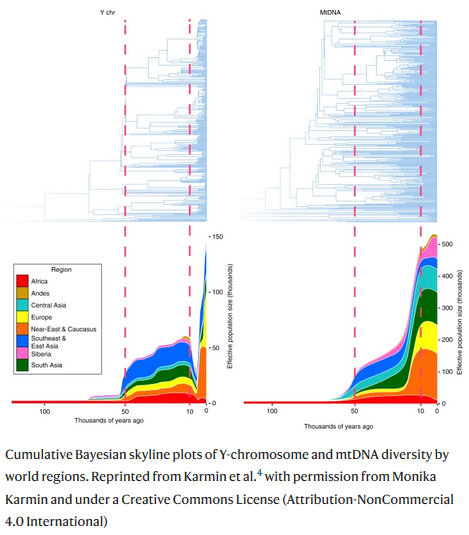

So, take a look at the image above. It is taken from a 2015 article by Karmin et al. There is a lot of information in that figure, but let's concentrate on the left graph. It shows the degree of diversification of the human Y-chromosome over time. You know that the Y-chromosome is something that only males have in humans, so the curve is roughly proportional to the active male reproducing population. The more diversified it is, the more males there are around, reproducing. Be careful: this is not the total male population. It is the population of those males who reproduce. Males who never mate with a fertile female don't appear in the graph. Note also that females are tracked using their mitochondrial DNA that they inherit from their mothers.

As you can see, the population of reproducing males is always smaller than that of the females (right graph). That doesn't mean that the total number of males (reproducing + non-reproducing) is smaller than that of the females -- for all we know, these numbers have remained comparable over human history. It seems that human males always have more competition and more troubles to reproduce than females (if you are male, you understand what I mean). So a sizable number of males always disappear from the genetic history of the species, even though they did exist and maybe they were also sexually active. It is just that they left no descendants.

But the impressive feature of the male curve above is the dip that takes place between 7,000 to 5,000 years ago. Hard times for males: only about one reproducing males out of 20 reproducing females. Ouch! (or maybe not so much of an ouch for those who did reproduce, who had 20 females each). That's weird: how can that be?

As always, we should take into account that all scientific results are affected by uncertainty. But this work seems to be solid and so far it has not been challenged. So, the question is, what happened that made our female ancestors so selective in choosing just one male in 20 as the father of their children?

You bet that a lot of hypothesis have been proposed to explain this catastrophe that hit human males in their reproductive success (but, again, it doesn't mean they didn't have female partners, just that they didn't mate with them when they were fertile). But what happened? An epidemics? The wrath of God? The spread of the fashion of monastic life?

It is a long, long story and we are far from having understood this pattern. But I think that a 2018 paper by Zeng et al. gave the correct interpretation. It all has to do with demes.

One more paragraph, one more thing to learn: what the chuck is a "deme"? Well, it is a known concept in biology, although not so common for most of us. Basically, a deme is a relatively stable group of individuals who often mate within the group and rarely outside. In human terms, you may think of a deme as the equivalent of a "tribe" or a "clan."

A characteristic of human demes is that they are often patrilinear: that is, they are dominated by a male hierarchy: there is a patriarch on top, his son, grandsons, and maybe great-grandsons. The females are more mobile. They practice exogamy, that is they tend to marry outside the deme (clan). The exchange of females among tribal groups is well known in anthropology.

Now, you see here the holobiont emerging: a deme is a kind of a holobiont, we might call it a "meta-holobiont" in comparison to the normal human holobiont. But a holobiont is a holobiont is a holobiont. It is a group of organisms that collaborate in a symbiotic structure. Not just that, but demes practice "holobiont sex" by exchanging genetic material in the form of female organisms. See how many patterns tend to repeat? Wonderful!

Here goes the explanation by Zeng et al., that I think makes a lot of sense. As all holobionts, demes have a finite lifetime. They can die because of various natural reasons, starvation, disease, etc. Or they may be killed by aggressive neighborhood demes. And here is the trick. In a deme, there is very little differentiation in the Y-Chromosomes. The males are all related to each other and you know that brothers all have the same Y-Chromosome. So, the deme dies, the Y-chromosome dies. How sad! Those males who were part of that deme don't pass their Y-Chromosome to their descendants, so they disappear from the human genetic history. But so is the way things are. The great holobiont called Gaia loves life, but She knows that there cannot be life without death.

But the death of a deme doesn't mean the disappearance of the female genetic imprint. Not at all. Since females practice exogamy, likely, the females of a dead deme had sisters in other demes that survived. Besides, killing a deme in war doesn't mean that the winners exterminate all the females, not at all and for good reasons! Males consider the females as a war prize. Nowadays we tend to think that killing males and raping their females is not a very nice behavior, but it was very common in history (and still is).

And here goes the final trick that explains the whole story. The drop in the reproducing male number takes place in a period of great expansion of the human population. It means that the demes were closer to each other and fighting for increasing scarce resources. It meant holobiont-style selection. Those demes that were less efficient in exploiting the available resources, and also less effective in war, disappeared, and with them a lot of Y-chromosome lineage. And that's what you see in the curve. Amazing!

But then, what happened that restored the chance of reproducing for human males? Well, there came the age of kingdoms, and then the age of empires, and kings and emperors don't like clans to fight against each other. They want all the males to fight for them, and that changed everything. Another long story that I'll tell in another post. But all these stories that deal with holobionts are fascinating!

And here is how Conan the Barbarian interprets deme competition

Genghis Khan would give Conan the Barbarian a run for his money:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/2/mongolia-genghis-khan-dna/

I know. Conan's speech was inspired on something that Gengis Khan said. And probably we all have more genes inherited from Gengis Khan than from Conan the Barbarian!

Delete