The human mind is the most complex entity we know in the whole universe. One of the fascinating things about it is how it has been evolving over time. What could have been the thoughts of a bronze age warrior? What thoughts did an ancient hunter-gatherer think? Why do we think the way we do, nowadays? As Sir Thomas Browne said, these are puzzling questions, but, like the song the Sirens sang, not beyond all conjecture. And here I am presenting a sweeping review in this area that starts with the work by Julian Jaynes on the mind of our remote ancestors, connects it with the most recent result of genetic studies, and even tries to peer into the future: how will the human mind evolve? Another question not beyond all conjecture. We may be moving toward much more complex and intricate forms of empathy than those we know nowadays.

The Mind

The mind is a tool, this much is clear. Of course, it is a special

tool, able to do many things in many fields. But it is a tool and it has

evolved to perform the tasks it performs. Do you remember Darwin's

finches? They are birds with beaks of different shapes that were

the source of inspiration for Darwin's idea of evolution: the beaks

adapted to the different kind of food eaten. The human mind does the same. If it is like it is, nowadays, it is because it

is functional to what it does.

That applies also to the entity we call consciousness. We can define it as the capability of "modeling oneself" just like we can model other people's behavior in order to predict it. You probably heard the story of the "mirror neurons," brain structures specialized in understanding the behavior of other people. In a way, it means reading other people's mind. Your dog can do the same: dogs have mirror neurons, too. You can use the term "mirroring" or also "modeling." It doesn't matter the term. if you can model other people's behavior, you have a certain degree of empathy. And, very likely, high empathy and self-consciousness go together. They are two axons of the same neuron.

Empathy is surely useful for us in many circumstances (also for dogs). You need to know if the person you have in front is there to help you or he wants to use his battle-axe on you. But that doesn't require much effort in terms of sophisticated mind-reading. Where modeling truly shines as an evolutionary tool is in the mating game. At least in our modern world, the competition for mates is fierce and ruthless and it involves many factors. Surely money and status count, but empathy does a lot as the capability of mirroring your perspective mate means behaving in a way that you know that he/she will appreciate. Ask any pick-up artist about that and he'll confirm that it is the tactic they use. Also, if you ever chatted with a professional sex worker, you may have noted how they have an uncanny ability of reading your mind and say exactly what they know will please you. The whole game is played by modeling another person's mind inside one's own.

So, it is no surprise that most of the modern literature and fiction deals with what we call "romance," men and women getting together. We seem to be deeply interested in the courtship rituals and about everything involved with it. It is one of the top skills of our mental arsenal. But have we always been like this?

The Evolution of the Mind

At which point

in their evolutionary history did humans develop this exquisite ability of reading each other's minds -- including their own -- that we have today and we also call empathy? There are cartoons that describe cavemen using their stone axe to

stun a woman before pulling her by the hair all the way into their cave. But that's of course a little unlikely to have ever been our ancestors' behavior, to say the least! But how did cavemen woo their women? Of course, the entity we call the "mind" leaves no fossil record, so what do we know about the empathy capabilities of our remote ancestors?

The first to pose this question was Julian Jaynes with his "The Origin of Consciousness and the breakdown of the bicameral mind"

of 1976. It was a milestone in the field: Jaynes analyzed ancient written records and he

concluded that the people living during the bronze age were

not really "conscious" in the modern sense of the term. They had what Jaynes called a "bicameral mind."

They would "hear voices" in their minds and act accordingly, but we have no

evidence that they had the kind of self-recognition that we normally

have today.

The idea of the "bicameral mind" as described by Jaynes has been often criticized and, indeed, there is no proof that the inner mechanisms of ancient minds worked the way he proposed. But it doesn't really matter whether the "voices" are the result of the interaction of the two halves of the brain or they originate in some other sections of the brain. The point is that the behavior of the people described in such documents as the "Iliad" or some books of the Bible is completely different from that of modern people. The ancient just seem to lack empathy, they act like automata, without evident feelings of love, compassion, or concern for other people. In modern terms, we would define bronze age people as "autistic." Maybe it is a literary style, but Jaynes' idea that people truly behaved in this way makes a lot of sense.

Just as an example: think of the Iliad.

The story start with Paris, a Trojan prince, stealing Helen from her husband,

Menelaus, king of Sparta. Then Paris is killed, and Helen marries another Trojan, Deiphobus.

Finally, Menelaus kills Deiphobus and takes Helen back. Does the Iliad report of anyone caring

about what Helen feels during these events? Was she unhappy, concerned, sorry, or what? No -- nobody gives a war

cry about that. Another example: consider the case of Tamar and Judah,

as reported in the Genesis. In the story, the only problem for Tamar

is how to give children to Judah's clan despite the death of her first

and second husband, both sons of Judah. And nobody cares

about what Tamar feels. Nor, there is any feeling or care for what Tamar's husbands feel, or pity for their fate.

Now, let expand the discussion a little. Jaynes had only written data, so his analysis couldn't go further back than the 3rd millennium AD, more or less. Before that age, there are no written records, at most pieces of statuary that might be interpreted in various ways, but that don't tell much to us about how people thought or behaved at that time. But we now have genetic data that, amazingly, give us a chance to go well beyond the "literacy limit." I refer to the recent discovery of the "Y-chromosome bottleneck" in humans (Karmin et al., 2015). I described these findings in some detail in a previous article on "The Proud Holobionts." Here, let me summarize these results.

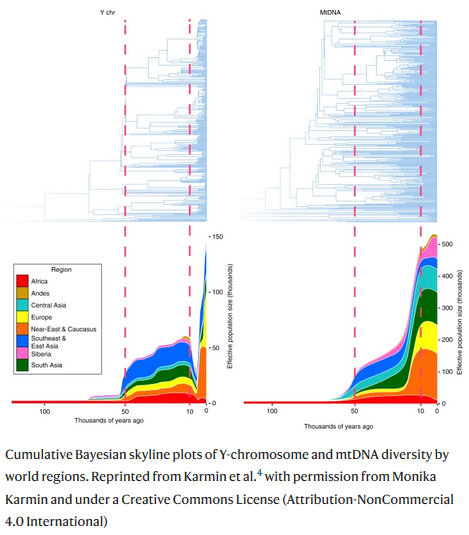

The figure above, (Karmin et al., 2015) reports the degree of diversification of the human

Y-chromosome and of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) over time. Both are elements of the genome that are passed only from male to male (Y-chromosome) and female to female (mtDNA). So, the curves are roughly proportional to the active male/female reproducing population.

For most of the record available, some 50 thousand years, the

population of reproducing males is smaller than that of the

females, roughly a factor of three. It doesn't mean that there were less males than females in these populations. Then as now, the male/female ratio for the people alive at any given moment was approximately equal to one. But not every human being manages to leave descendants: many disappear from the genetic history of the species. For some reason that would be long to discuss, females are normally more successful than males at that and that's what we see in the curves of the study.

But the study shows an impressive

and unexpected feature. A "bottleneck" in male diversification that takes place between

7,000 to 5,000 years ago. In this period, there was only about one reproducing male out of 20 reproducing females.

If we now compare with Jaynes' data, we see that he placed the bicameral mind as existing approximately during the 3rd-2nd millennium BCE, while the breakdown took place during the late 2nd millennium, roughly with the end of the bronze age. So, Jaynes' time window overlapped in part with the bottleneck. What he was seeing was the climbing side of it. He saw modern consciousness appearing (re-appearing?) with the male reproductive effectiveness gradually regaining the normal value of 1:3 with respect to the female effectiveness after a period of eclipse. But what does that mean?

Interpreting the data

We said that the conscious

part of the human mind is mainly a tool used to find sexual partners. So, the mind must have adapted to the social and economic structures of society as they changed and evolved. Then, let's start from the beginning, the left side of the curve reported by Karmin et al. from ca 50.000 to 10.000 years ago. We see that during that period the average the reproductive success of human males was about the same as it is today, that is one male reproduced for about three females .

We know in those remote times, humankind was mainly practicing a hunting and gathering lifestyle. What were people's minds like at that

time? Of course, we have no written records from those times. But we still

have hunter gatherers around in our world, so that we can have some idea

of how they think. Helga Ingeborg Vierich

has lived with hunter-gatherers and she reports that they are kind and

considerate, and rarely polygamous. In their societies, males have

about the same chance as females to marry outside the group. Women

have positive roles in society, separate but not inferior to the roles of

males. On this point, I can also report my personal experience with the

Roma (the Gypsies) who are perhaps the closest approximation to a

hunter-gatherer society existing in Europe nowadays. In terms of empathy, I

can tell you that their skills in reading the mind of a gajo (a non-Rom) are nothing less than exquisite. They need these skills in order to survive in a world where the gaji are a large majority. If empathy is a useful skill in a monogamous, relatively

egalitarian society, then our hunter-gathering ancestors clearly had it, just like our modern hunter-gatherers do (and the Roma, too).

Then, there came the "bottleneck" that corresponds approximately to the end of the Neolithic and the start of metalworking, first copper then bronze. As it normally happens, technology changes society, sometimes very deeply. The bronze age saw people moving away from the traditional

hunting-gathering lifestyle to that of farmers and pastoralists.

It is normal (but with plenty of exceptions) that pastoralists tend to

live in patrilinear "demes" (you can call them "clans"), a term used in

biology to indicate groups in which individuals tend to mate mainly with

other members of the deme.

In

human patrilinear demes, males tend to remain within the deme, while

females are more mobile and move from a deme to another (it is called exogamy). In this kind of society, women marry a clan, not a person, just like Tamar did in the Biblical story. Even in the case of Helen of Troy, the story of her abduction may refer to a form of exogamy.

In

this kind of patrilinear societies, we can imagine that there is

little need for either males or females to develop the kind of empathy that we moderns

need. Neither Paris nor Helen are reported in the Iliad to have been "in love" with each other in the modern sense of the term. There is nothing romantic in their relation. In general, if a woman marries a clan, then she doesn't care

whether the male they mate with is nice, considerate, and gentle. What

counts is how many sheep the clan has. Maybe this is a little schematic

(a lot), but it seems to fit with what we know of the age described by

Jaynes.

These genetic data are in line with the interpretation that the age of the bottleneck corresponded to an increasing population of pastoralists living in patrilinear demes. This is explicitly discussed a 2018 paper by Zeng et al. They explain the bottleneck as due to evolutionary competition between demes, rather than individuals. A deme can "die" either because it is outcompeted by the others for scarce resources or because its members are killed in battle. Since the males in a deme are closely related to each other, there is a good chance that, when the deme dies, their Y-chromosome disappears from

the human genetic history. Females, instead, owing to their exogamic habits are more likely to have their genetic signature survive, being spread over several memes.

Can these social changes

affect the genetic build-up of the human mind? We cannot say for sure, but don't forget how powerful evolution is in shaping the functioning of living creatures. The whole "bottleneck" episode

lasted a few millennia and Cochrane and Harpending suggest in their "The 10,000 year explosion,"

that the human genome could change significantly in such a short time.

For instance, they note that bronze age people had a significant brow ridge that was later mostly lost. Human females of the late bronze age didn't seem to like this feature very much in their males, just like modern human females don't. But no amount of cultural change can make you gain or lose a prominent brow ridge. It can only be genetic.

But it is not really fundamental to decide whether the big

changes we see across the bottleneck are genetic or cultural: let's just

say that they occurred, quite possible because of a mix of the two factors. Then, everything clicks together, more or less. The bottleneck was caused by the rise of a patrilinear society organized in small demes, then it disappeared when the demes were superseded by new social organizations: cities, states, and empires. Kings and emperors didn't want their subjects to fight tribal battles against each other. So, they broke the deme structure in various ways -- they never were able to eliminate them completely, but their importance was enormously reduced. With this, the old bronze age "bicameral" mind became obsolete. And evolution did its job: what is not needed or is harmful, disappears.

The rise of monogamy

Over the past 2-3 thousand years, we see a gradual tendency for rigid clans to disappear and a certain degree of egalitarian society developing. Monogamy becomes more and more common, at least for the average people (kings and emperors are not bound to their own laws). Monogamy was not only a social custom, but often enforced by laws and by religious commandments. The main reason for this development is that monogamy is a useful feature for a military empire (and all empires are). Armies need soldiers and cannot tolerate that soldiers fight with each other for females. Instead, if every male has one female, at least on the average, there is no need for internecine fighting among males to hoard as many women as they can. And so all the men of the empire could be turned into fighters to use against external enemies. Then, if the state takes care of enforcing monogamy, soldiers can embark in a long campaign in remote lands knowing that, at least theoretically, their wives will be waiting for them. The Romans, the paradigmatic military society in history, were strictly monogamous, at least with respect to the marriage of free Roman citizens. That was typical for most empires in history.

Monogamy may be one of the main reasons for the development of the emphatic mind we all have. If you live in a relatively egalitarian society, you have a large number of potential partners: choosing the best one becomes a difficult game that requires sophisticated empathic capabilities in order to convince a perspective mate that one is the right partner for him/her. It is a game where you have to deploy all sorts of strategic skills to optimize your chances. And it is a risky game: you may not be able to find the right partner or you may need to settle for a less-than-perfect partner. You may know the story of the man who had decided he would never marry until he could find the perfect woman. And after much searching, he found her. The problem was that she was looking for the perfect man!

So, you see how difficult the game is, and you probably experienced that yourself. For sure, bronze age people wouldn't do too well at it. Imagine a bronze age warrior walking into a modern ballroom.

He would stand in front of a girl and state, flatly, "I have plenty of sheep and you are to be my woman." Not exactly the best strategy to win the hearth

of the prom queen.

Then, of course, monogamy was never perfect and it was always accompanied by the activities that we call "philandering" for males. For females, we use terms such as strumpet, harlot, trollop, slut, or whatever. It doesn't matter, it is still the same game and it requires empathy. Married men are easily convinced by women who woo them, while married women have sophisticated ways to let men understand that

they are happy to be wooed. But no modern woman would be interested in an affair with a bronze age man, no matter how many sheep he has. And no bronze age woman would be interested in an affair with a man who doesn't have any sheep. Empathy rules the game, that much is certain.

So, we can explain why the Western civilization has developed so many examples of what we call today "romantic fiction," from the saga of King Arthur, to modern telenovelas. It is probably a form of training for young minds that emphasizes such feelings as romantic love and typically involves a couple of lovers who face all kinds of obstacles but who, eventually, are reunited all thanks to being faithful lovers. This kind of fiction would be most likely totally incomprehensible by our ancestors. Imagine asking Tamar (the one of the Genesis) "but do you love your husband?" I can see her face looking like if you had asked her, "do you like French cuisine?" Some people have tried to cast Tamar in the role of a modern character with results, well, lets say not completely satisfactory (more details at this link).

The Final Question: How about the future of the mind?

After a few thousand years of prevalence, monogamy is clearly in decline. It never was perfect but, once, it was enforced by law and customs and, in some countries, you can still be stoned for being an adulteress. Even divorce used to be illegal in many Catholic countries up to recent times. Today, these rules have mostly disappeared, although 19 US states still define adultery as a crime and there exist two countries in the world where divorce remains illegal, the Philippines and the Vatican.

This relaxation of the monogamy rule can be explained as the result of the decline of the role of males as fighters. Up to a certain time, not many decades ago, wars were won by the state that could line up the largest number of poor clods in uniform and have them march forward while being shelled by the enemy artillery. That's not so important anymore and the development of drones and war-robots has made the very concept of "soldier" obsolete.

The current situation is basically unheard of in the history of humankind. There has never been an age in which males had become useless as military machines. This point may not have been understood by the leaders, yet, but it seems clear that, if there is little or no need males as soldiers, there is little or no reason to enforce rigid codes and laws on sexual behavior for them and their wives.

That's rapidly modifying the standard way of thinking about sexual codes of conduct, especially in the West, even though we can probably rule out that it is modifying the human genetic code (yet). In any case, the current way of thinking of Westerners is as far away as that of bronze age warriors as it could be. The focus on mind-reading is being turned to one's own mind and modern Westerners can be defined as extreme cases of narcissists, interested only in their own well being. It is what we call the "me-generation."

The problem with the me-generation is that it is generating a class of people who think they can do everything that pleases them. And the only thing that's worse than a narcissist is a rich narcissist. One of the things human males like to do is to hoard women in personal harems, as it was the use in some societies in the past. So, if a male is both a narcissist and he has enough power in the form of money, what can stop him from having multiple female partners in the form of occasional or stable concubines, or even in the form of a traditional harem?

The current laws and customs prevent the men in the most visible

positions from explicitly expressing their sexual habits, but if you look

at the recent sex-scandal involving Jeffrey Epstein, you can notice that there

are things going on with our leaders that don't appear in the media. Even without concubines or harems, already now, we might say that in the West the elites enjoy "time-dependent polygamy," in the sense that they periodically switch from an older wife to a younger one. That, of course, deprives young and poor males of suitable female partners, but it is the law of money. In time, we might see the development of a rigidly stratified society where the elites accumulate women just like they accumulate money.

Then, if women are seen as accumulated capital, there follows that methods are needed to make sure that they are not stolen or lost. Eunuchs are a traditional way to keep women in their place -- and they also help solving the problem of excess males. But there are even more invasive methods to control women. Several societies in our

time practice "female genital

mutilation." The idea is that if a woman feels pain during sex, she will

be less interested in

cheating her husband (or harem master). In its extreme form, infibulation, the woman is

treated like a coffer that can be locked and unlocked at will. Female genital mutilation is not so popular nowadays in the West but, who knows?

Fashions change so rapidly!

Chances are that someone who owns a harem of infibulated women doesn't think of them in terms of romantic love, not any more than one of our billionaires have romantic feelings for their stock portfolio. Indeed, it is often reported that the rich are nasty, unfeeling, and uncaring for others. That's what you would expect. Why would the rich need to care for others? They don't need empathy-based skills. Then, the women in a harem would hardly be thinking of their master as someone to love in romantic terms. To say nothing about the eunuchs.

So, if these habits were to become the rule in the future, then the human mind could change, culturally and perhaps even genetically. Evolution, cultural and genetic, does it work of eliminating those features that are not needed, think of the wings of the dodo bird. So, the sophisticated empathy capabilities that we had developed over the past 2-3 thousand years could disappear in a few centuries. Then, future scientists may discover a second bottleneck in the human Y-Chromosome diversity and wonder what caused it.

But there are other possibilities and it is not farfetched to think that the next step for society will be to discover that the modern obnoxious alpha-males and their manic sex-habits are not only useless, but expensive and dangerous. So why don't we just get rid of most of the males, leaving around just the tiny number needed for reproduction? After all, it is a choice that ants and bees made millions of years ago. Their social organization is called "eusociality" and human society already has some of its characteristics, so that it can be defined as "ultrasocial".

Is it possible to transform human society in such a radical way? Why not? We evolved, and we keep evolving. Already, the features of our society would be completely unrecognizable to someone living just a few centuries ago. And if ants and bees (and also the naked mole rat) evolved toward eusociality, there is no reason to think that we can't follow the same steps. Nate Hagens has been discussing how our society is already moving toward what he calls the "superorganism" -- a term used also for anthills and beehives.

Our society is already much more complex than the patrilinear demes of the

Bronze Age and a future eusocial version would be even more complex. In the network of complex subsystems we live in, and in those in which we may live in the future, empathy

deals with many more things than just finding a sex-mate. As Chuck Pezeshki notes, empathy is not a rigid concept, it is a process that evolves toward more complex and sophisticated forms (this figure is from Pezeshki's blog).

So, humans might be moving toward a version of empathy that will be highly sophisticated and structured as it can be in a universe that we are perceiving as more and more complex, a hierarchy of systems that we call "holobionts" and that culminates on this planet with the highest level holobiont of all, the entity we call sometimes "Gaia." Developing this kind of empathy could place humans truly in harmony with nature and with their own species. It would be a form of empathy that we can imagine as connected to what we call today the "religious experience." And maybe they'll perceive things that current humans cannot even imagine. It would be the "revelation through evolution," a concept that Michael Dowd has perceived. The Goddess Gaia revealing herself in her full glory,

And onward we go, evolving all the time.

___________________________________________________________

h/t Michael Dowd, Chuck Pezeshki, Nate Hagens, Maria Mercedes Sanchez, and Helga Ingeborg Vierich,